Portraiture, Kingship and Kemet: The case of Senusret Kakaure

It seems a little odd, when the majority of Egyptologists have no direct connection to Africa in regard to their own biological or cultural heritage, that they feel justified in deciding when a representation is or isn’t of a person of African descent.

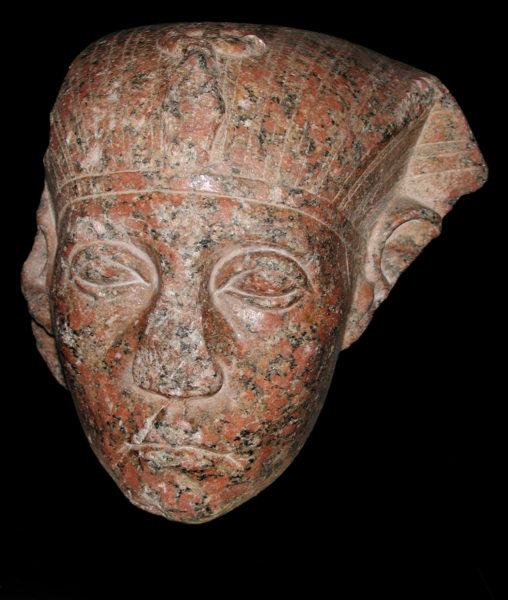

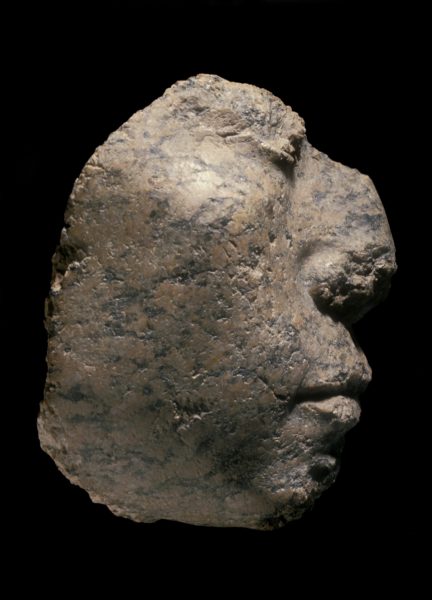

The ruler illustrated in this post is a case in point. It represents Senusret Khakaure, who is now known as Senusret III. He was a fifth ruler of Dynasty 12, which belongs to a period now referred to as the Middle Kingdom, and ruled Kemet from around 3800 years ago (circa 1872-1853 BCE). His strong jawline, hooded eyelids and prominent cheek bones have led many people to recognise facial features that are typical of some indigenous African people, and people of African descent.

Now it should be the case that you don’t need a qualification to decide whether a statue represents someone of African descent, no? Well, that doesn’t seem to be the academic consensus in the case of Ancient Egyptian sculpture. Since the 1990s it has generally been assumed that images of kings are not true likenesses of the people they represent.

I should state from the off-set that I do not subscribe to this point of view and whilst I am prepared to concede that rulers, from any culture, are typically represented in an idealised way, I really do not understand why a portrait would look nothing remotely like the subject. Particularly when there is such a variety amongst Ancient Egyptian royal sculpture.

I adopted this point of view very early in my career as an Egyptologist. My doctoral thesis was on Egyptian royal sculpture and I subsequently spent some years continuing to research this particular area. I am confident that I could correctly identify an image of any Ancient Egyptian ruler. I can do so, because each had a very specific ‘portrait’ type.

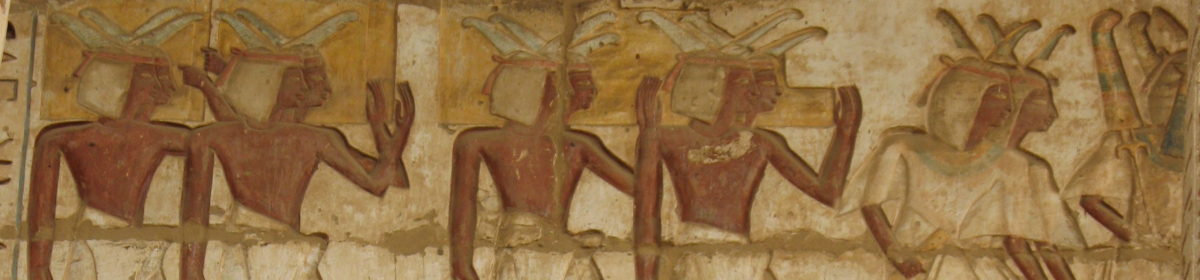

There was a good reason for this phenomenon. Life-size stone statues, (such as those above) were often placed at the entrances to temples or palaces with the intention of promoting the King. Inscriptions were not always visible on statues and so the iconography (symbols) and the facial features needed to also play a part in assisting with identifying who the statue represented. How then are the features of Senusret III typically explained?

Realistic, symbolic or psychological portraits?

In 2015 the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York held an exhibition entitled: Ancient Egypt Transformed. The Middle Kingdom . The key issues relating to Middle Kingdom portraits are contextualised in an essay for the catalogue by Dorothea Arnold entitled: Pharaoh. Power and Performance (Ancient Egypt Transformed. The Middle Kingdom, edited by A. Oppenheim, D. Arnold, D. Arnold, and K. Yamamoto. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 68-72). They are as follows:

- Realistic– Egyptologists Cyril Aldred and Jacques Vandier who wrote, in the 1980s, on the subject of portraiture in Kemet dating to the so-called Middle Kingdom concluded that the portrait features on statues from this period were realistic representations of the kings.

- Non-realistic– in relation to non-idealised portraits on funerary representations dating to the earlier period of the so-called Old Kingdom, Bernard V. Bothmer concluded that no representations from Kemet should be called ‘portraits’.

- More recently, Egyptologists have interpreted features on the sculptures of Senusret as coded messages– for example the prominent eyes representing a vigilant king.

- In 1996 Egyptologist Jan Assmann, put forward the idea that these portraits represented the inner character of the kings and were psychological.

More recently, and as Arnold concludes in her essay, specialists in sculpture generally accept that these royal representations draw upon the actual appearance of the king, but within an acceptable framework so that he can be identified as such by people who looked at the statue. Arnold writes the following:

… it is very difficult to imagine that Senwosret III’s eyes in his official image did not reflect his own peculiarly shaped eyes in real life… The faces of Senwosret III… are best understood as recognizable images of these pharaohs with some realistic details formalised in the particular intellectual climate. (p. 71)

I have included this quote because a number of friends and colleagues who have questioned professional Egyptologists have met with a response that suggests portraits from this period are to be dismissed as non-realistic representations. In other words when asked if Senusret really looked like his statues, they are told that this is not the case. The question often arises because people of African descent recognise the portrait features on these statues as similar to their own. Therefore, to deny that the statues look even remotely like their subject, is to deny their African origin.

There is one key issue that no-one seems to have addressed. Whether these ‘portraits’ are realistic or idealised representations, the overall appearance of these statues (their profiles, facial features, and also where hair is represented) suggests very strongly that they represent indigenous African people. Why would any sculptor show their kings in this way if they were anything other than African?