Today I received a statement from Dr Neal Spencer, Keeper of the Department of Ancient Egypt and Sudan, with regard to the British Museum’s policy on displaying Egypt as part of Africa:

The Department of Ancient Egypt and Sudan at the British Museum has, in the last 15 years, focused much of its research on the relationship between Egypt and Nubia, from Prehistory through the Medieval Period. The geographic (Egypt and northern Sudan) and chronological scope of that research is of course a reflection of the collections material we hold that research can be undertaken on, and the research specialisms of staff within the museum. Surfacing that research in galleries is not always straightforward, as some of the material is fragmentary and difficult to display, but we publish widely (both online and in print) and run an extensive programme of lectures, gallery tours and conferences (seewww.britishmuseum.org with further links to online content and publication lists).

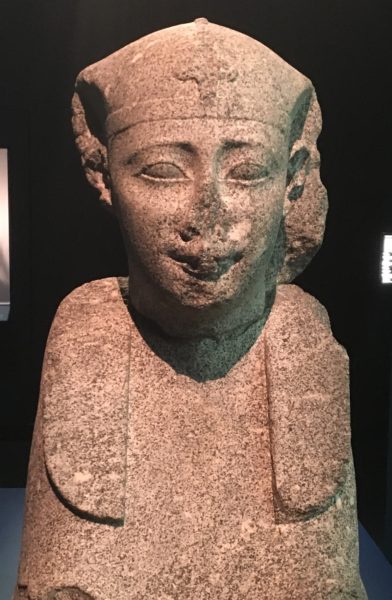

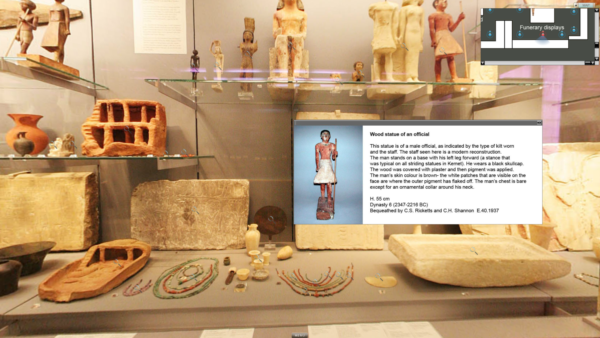

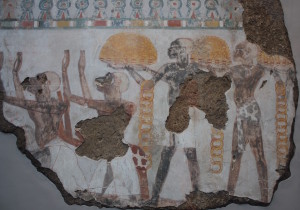

The present-day Egyptian galleries are arranged thematically – looking at life (and idealised life) in New Kingdom Egypt (Room 61, Nebamun), funerary beliefs in Egypt (Room 62-63), prehistoric Egypt (Room 64) and Egyptian temple/tomb sculpture (Room 4). Within those galleries and the chosen themes and space, there is limited scope to discuss how these themes relate to wider Africa, or indeed regions that Egypt was in contact with beyond Africa. A bioarchaeology section in Room 63 does highlight how future research might tell us about migration patterns within and beyond Africa, which would of course be relevant. The Room 4 display does feature some objects relating to Dynasty 25 and the Kushite state and culture.

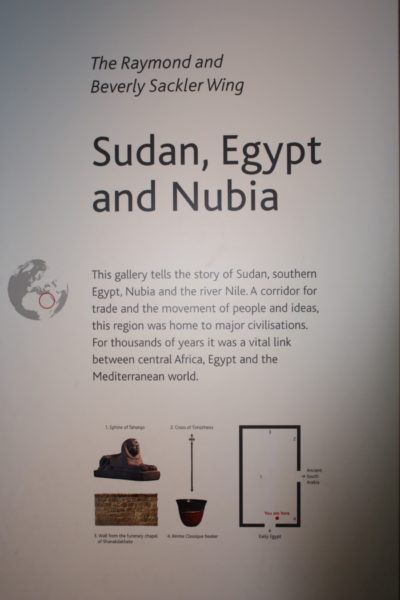

Room 65 is the exception, as the chosen theme here expressly looks beyond Egypt to explore its relationship with areas further south, across a period spanning prehistory to the Medieval era. This gallery – entitled “Sudan, Egypt and Nubia” – looks at the distinct aspects of Nubian and Egyptian cultures, alongside shared elements, and how they were at times entangled, with ideas, iconography, art, craft, technologies and so on travelling in both directions. This gallery highlights Egypt in the context of another great and (importantly) contemporaneous African civilisation, using objects from the collection.

Research, collections and display on Africa at the British Museum are not limited to the Department of Ancient Egypt and Sudan, but are ongoing across the Museum. Egyptian objects (principally of 19th and 20th century date) are also featured in the Living and Dying gallery, and the Africa galleries. Finally, we are currently in the process of creating a collection relating to 20th century Egypt, with associated research. This very much places Egypt in its global context, and an emerging story within that is around Egypt’s engagement with sub-Saharan Africa during the 20th century – something that is less often highlighted than its relationship to the Middle East, Europe, USSR and USA. The outputs of this project are still being defined, but might include small displays, a book and digital content.

We are very aware of different interpretative frameworks for how Egypt is part of Africa at different periods, and around the reception and interpretation of ancient Egypt, but none of our galleries focus on interpretative frameworks nor the historiography of research. This current situation in no way precludes future displays on such subjects, whether in permanent galleries or exhibitions.

We seek to be open to debate, new ideas and discussion. Public programming and online content is naturally quicker to reflect such things (for example, inviting Sally-Ann Ashton to give three lectures at the British Museum on the subject of African-centred approaches to Egyptology), as gallery interpretation can take time to change, for logistical reasons. The current displays and information vary in date from 1979 to 2015, depending on the individual gallery, but as we have opportunities to update those, we will of course consider new research and perspectives.

Neal Spencer, Department of Ancient Egypt & Sudan, British Museum