Portraiture, Kingship and Kemet: The case of Senusret Kakaure

It seems a little odd, when the majority of Egyptologists have no direct connection to Africa in regard to their own biological or cultural heritage, that they feel justified in deciding when a representation is or isn’t of a person of African descent.

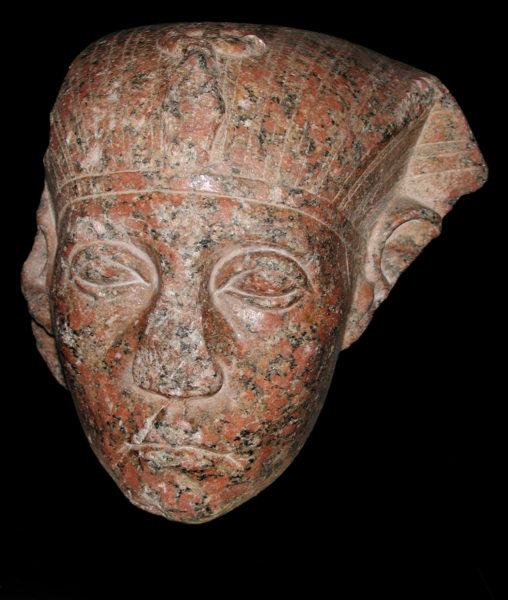

The ruler illustrated in this post is a case in point. It represents Senusret Khakaure, who is now known as Senusret III. He was a fifth ruler of Dynasty 12, which belongs to a period now referred to as the Middle Kingdom, and ruled Kemet from around 3800 years ago (circa 1872-1853 BCE). His strong jawline, hooded eyelids and prominent cheek bones have led many people to recognise facial features that are typical of some indigenous African people, and people of African descent.

Now it should be the case that you don’t need a qualification to decide whether a statue represents someone of African descent, no? Well, that doesn’t seem to be the academic consensus in the case of Ancient Egyptian sculpture. Since the 1990s it has generally been assumed that images of kings are not true likenesses of the people they represent.

I should state from the off-set that I do not subscribe to this point of view and whilst I am prepared to concede that rulers, from any culture, are typically represented in an idealised way, I really do not understand why a portrait would look nothing remotely like the subject. Particularly when there is such a variety amongst Ancient Egyptian royal sculpture.

I adopted this point of view very early in my career as an Egyptologist. My doctoral thesis was on Egyptian royal sculpture and I subsequently spent some years continuing to research this particular area. I am confident that I could correctly identify an image of any Ancient Egyptian ruler. I can do so, because each had a very specific ‘portrait’ type.

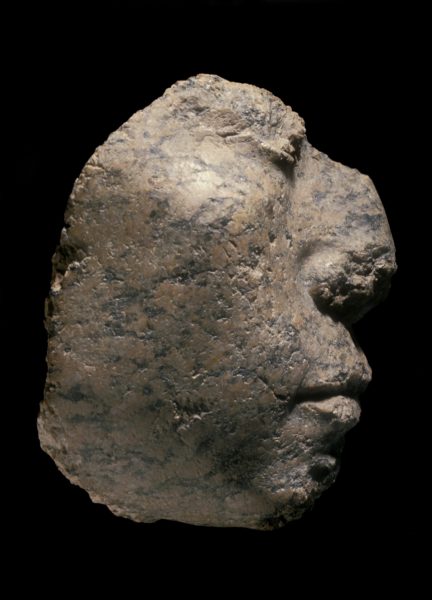

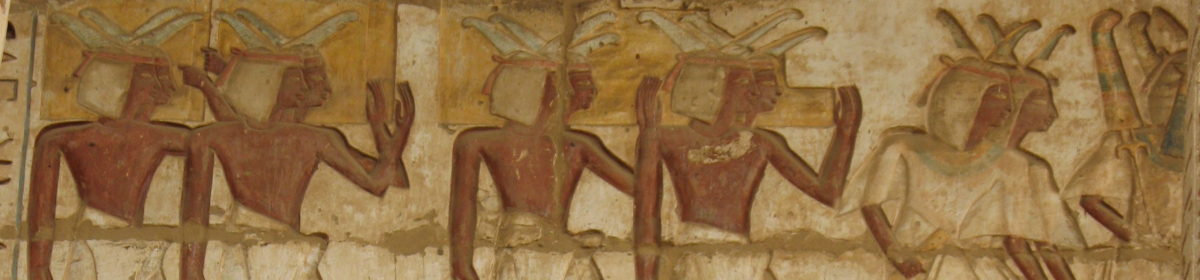

There was a good reason for this phenomenon. Life-size stone statues, (such as those above) were often placed at the entrances to temples or palaces with the intention of promoting the King. Inscriptions were not always visible on statues and so the iconography (symbols) and the facial features needed to also play a part in assisting with identifying who the statue represented. How then are the features of Senusret III typically explained?

Realistic, symbolic or psychological portraits?

In 2015 the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York held an exhibition entitled: Ancient Egypt Transformed. The Middle Kingdom . The key issues relating to Middle Kingdom portraits are contextualised in an essay for the catalogue by Dorothea Arnold entitled: Pharaoh. Power and Performance (Ancient Egypt Transformed. The Middle Kingdom, edited by A. Oppenheim, D. Arnold, D. Arnold, and K. Yamamoto. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 68-72). They are as follows:

- Realistic– Egyptologists Cyril Aldred and Jacques Vandier who wrote, in the 1980s, on the subject of portraiture in Kemet dating to the so-called Middle Kingdom concluded that the portrait features on statues from this period were realistic representations of the kings.

- Non-realistic– in relation to non-idealised portraits on funerary representations dating to the earlier period of the so-called Old Kingdom, Bernard V. Bothmer concluded that no representations from Kemet should be called ‘portraits’.

- More recently, Egyptologists have interpreted features on the sculptures of Senusret as coded messages– for example the prominent eyes representing a vigilant king.

- In 1996 Egyptologist Jan Assmann, put forward the idea that these portraits represented the inner character of the kings and were psychological.

More recently, and as Arnold concludes in her essay, specialists in sculpture generally accept that these royal representations draw upon the actual appearance of the king, but within an acceptable framework so that he can be identified as such by people who looked at the statue. Arnold writes the following:

… it is very difficult to imagine that Senwosret III’s eyes in his official image did not reflect his own peculiarly shaped eyes in real life… The faces of Senwosret III… are best understood as recognizable images of these pharaohs with some realistic details formalised in the particular intellectual climate. (p. 71)

I have included this quote because a number of friends and colleagues who have questioned professional Egyptologists have met with a response that suggests portraits from this period are to be dismissed as non-realistic representations. In other words when asked if Senusret really looked like his statues, they are told that this is not the case. The question often arises because people of African descent recognise the portrait features on these statues as similar to their own. Therefore, to deny that the statues look even remotely like their subject, is to deny their African origin.

There is one key issue that no-one seems to have addressed. Whether these ‘portraits’ are realistic or idealised representations, the overall appearance of these statues (their profiles, facial features, and also where hair is represented) suggests very strongly that they represent indigenous African people. Why would any sculptor show their kings in this way if they were anything other than African?

Great article! yes same with Huni bust, 3rd dynasty. Kufu also to a lesser extent, all appear with African features. I would say to those academics who cant acknowledge the obvious African features going all the way back to Early dynastic period, they need to hang out more with black people.

And by the way, it is evidence, its glyptic evidence.

Having researched this subject obsessively over last year i am actually shocked at the conspiracy of silence within academic circles which is to deny any possible references to race, especially when it might indicate Kushites or Africans in general.

Every reference from historical textual record, for instance the “black headed Sumerians”, or the “Curse of Agade” which mention Meluhha as the “black land”. or the word Egyptians used for their home – Kemet (Black land). Believe it or not all these references to “black” are explained away as referring to something else. It’s quite absurd.

Another interesting aspect re identity are the Hyksos. The assumption is that they were Semites, from Levant, or thereabouts. The term used for them Heqa Kasut or Kaset, is translated as a generic “rulers of foreign lands”. But the root of the Kasut is suspciously similr to Kash, Kush, and likely the Sut or Set refers to the deity, which as is well documented at Avaris, under Apohis, were Set worshippers, above all else.

Whats also weird coincidence is Ahmose Stele which contains a summary of the dialogue between Apophis and a Kushite King, where he calls him “brother”. I;m not suggesting they were actual brothers, but it does imply that Apophis felt he had enough Kushite dna in his heritage to make that sort of call. Again I was debating this with an academic and they just say oh everyone called everyone else brother.

The amazing result of every reference to “black” in the textual record being explained away as nothing to do with race, or “black” people, is amusingly absurd, because the implciation then is that race played no part in anything, and no-one ever discussed it, or referred it.It was topic verbotten! How plausible is that?

I actually think there is a weird inverse relationship between the Indo European bandwagon, and the suppression of facts which suggest a much stronger and earlier Kushite influence in Egypt and what we call Assyria. There is plenty of evidence to support the argument that at least some of those supposedly Indo European kingdoms had Kushite or African origins. The narrative that these people just disappear without a trace smells pretty rotten. As per Occams razor, it is far more likely we have simply misidentified them.

As mentioned earlier about Meluhha. Even though we have textual evidence from Ashurnibal telling us where it is, farther South than the first cataract, can only mean Sudan, or Ethiopia; academics ignore the only empirical evidence, so that they can carry on with this Indus Valley myth. What is the point in archaeology and deciphering cuneiform if one is going to ignore what it says, and just write their own narrative? That isnt interpretation, that simply fake news, fake history.

Semantic propaganda techniques are now employed by academics as in terms like “near certainty” to put lipstick on pigs.

So what is it about Meluhha which makes academics act like Stepford wives? Its all about Africa., because Meluhha plays a large p[art in the textual record going all the way back to early Sumerian, Early dynastic. It would mean that Kush was not on the periphery, oit was central to events in Egypt and West Asia by early 3rd millennium BCE. Also a load of other toponyms in the record which appear to be in close proximity to Meluhha also need amending on the map.

It simply drives a charoit through the cherished euro-centric narrative re ANE history. Im hoping this is the only reason and we don’t have bunch of passive aggressive racists in ANE studies. This suppression is cultural racism on a really odious scale, and those academics who know the story is crooked, but dont want to rock the boat, or lose funding for all those Indo European studies, are as culpable as the those in control, or the driving forces of the agenda.

Anyways it was nice to read this, thank you.

“It seems a little odd, when the majority of Egyptologists have no direct connection to Africa in regard to their own biological or cultural heritage, that they feel justified in deciding when a representation is or isn’t of a person of African descent.”

What exactly is meant by that ? Would agree that when it comes to genetics and physical anthropology, Egyptologists are predominantly lay people but the statement feels like the authors using an identity politics way of framing things. It might of sounded better if instead of being critical of they’re identity (that they’re non-African) the author critiqued they’re discipline (Egyptology) for lagging behind in regards to genetics and physical anthropology.

The author of this site is a non-African Egyptologist but still produces good quality scholarship.

Identity plays a role in how we interpret. This is recognised in the social sciences, where it is common for academic authors to describe their own cultural, ethnicised and racialised backgrounds when reporting on research.

Absolutely but that doesn’t mean that some of the frameworks being used don’t have pitfalls.

Something problematic in both Eurocentric and African Centred Egyptology is that there are two camps of mostly western trained scholars competing over the use of the Egyptian past to determine the presentation of that past to the rest of the world, at times while excluding modern inhabitants.

There are also instances whereby white and black academics (and even lay people) exclude modern Egyptians from they’re heritage, both asserting them to be ‘Arab invaders’ and ‘Caucasians’.

Suddenly the idea of Africa being diverse stops.

This is why it is essential for whoever is presenting Ancient Egypt to consider how their own identity may impact on their interpretation, modern Egyptian people included. The dominant culture of modern Egypt is completely different in terms of religion, language, and culture (note I said dominant). Change on this scale isn’t exclusive to Egypt, and it presents a problem because we are only working with a small amount of information, and dependent upon our own knowledge (limitations) and experiences when we seek to interpret it. I have found over the years that the best way forward is for people from diverse backgrounds to come together and work. Sadly, for some reason that rarely happens.

Hi Dr. Ashton I was just wondering if you’ve ever come across any beaded collar necklaces The jewelry the Ancient Kemetian people wore is still being worn in Africa today

Hi Clinton, there are direct parallels, for example the use of cowrie shells- we find these on pre-dynastic necklaces, accompanied by beads. This cowrie shell is later copied in the form of faience and steatite beads. Like some other traditional African cultures beads are a sign of status, which is why so many survive because people were buried with them. I know that Karo women of Ethiopia wear cowrie bead necklaces. I recall seeing contemporary photographs of Fulani women wearing cowrie shells and I am certain there are many more from cultural groups in West Africa. Most of the collars that you mention, that I have seen, from more recent cultures, are not made in the same way as those from Kemet. Unless you have examples, in which case please do share the images! The importance of the connection is really in the shared-cultural meaning.

Sounds good to me. Excited to see your next post on the subject matter

Great post. I really appreciate the time and effort, you have made over the course of time establishing that ancient Kemet was a African civilization. But I have a question for you. What do you say to euro-centrics who claim that the ancient Egyptians were European Caucasians and they have the DNA evidence to back it up. Plus! Are there more recent genetic testing being done on pre historic or dynastic Egyptians to determine ancestry? Thanks

Hi Charles, thanks for your comment. That’s a really good question and if you don’t mind I’ll answer it in a post so that I can put the necessary links in. I’m not a biological anthropologist so I will be referencing the work of those who are better qualified. but will do my best to dedicate next week’s post to answer your question!