The colour black in Kemet

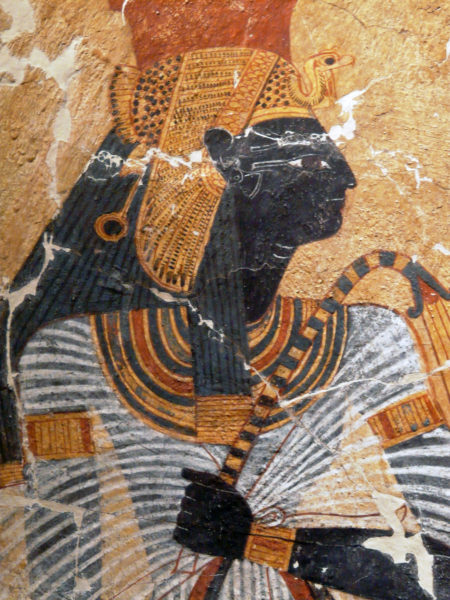

I asked my friend Dr Runoko Rashidi for some inspiration for a blog post and he very kindly sent me a copy of a photograph of the Royal Wife and Mother Ahmose Nefertari. She was the wife of the first ruler of Dynasty 18- King Ahmose Nebpehtire, who ruled from 1550 to 1525 BCE. She was also the mother of Amenhotep (I) Djeserkare, who ruled from 1525 to 1504 BCE. It was in the latter capacity as the King’s Mother that she was made a goddess. The relief is of interest of course because her skin is painted black rather than the usual brown.

The word Kemet literally means the Black land. The hieroglyphs above spell out the word and are accompanied by what we call a determinative (the circle and cross to the lower right of the word). In this case the determinative represents roads crossing and so a land.

In Kemet, black was associated with the night, with the Afterlife, and also with resurrection and rebirth. Black was also associated with fertility, we believe because it was the colour of the fertile soil that was deposited after the annual flooding of the River Nile.

Since the building of the Aswan dams the river no longer floods. However, even today it is possible to see how the river impacts on the terrain around it and how different this is compared to the surrounding desert escarpment. The annual inundation of the Nile was closely associated with the King of Kemet, and there were strict rules about when the ruler could and could not travel on the river.

Black and Divine

The relief above was found in a tomb at the workman’s village of Deir el-Medina. This was where the men who created and decorated the royal tombs in the so-called Valley of the Kings and Queens lived, and were also buried. These were highly skilled craftsmen and artists and when the elite in their own society died they were given elaborately decorated tombs. The tomb where the relief was found is now known as TT359 (TT being a shorter reference for Theban Tomb). It belonged to a man who held the position of Chief of Works named Inherkhau. He lived long after Ahmose Nefertari had ruled and commissioned two tombs; the second is now referred to as TT299. The tombs and the painting of Ahmose Nefertari were produced over 350 years after the Royal Wife and Mother’s death. Indicating that her role of goddess continued long after it was awarded.

If we look in detail at the painting we can immediately see that this is a representation of a goddess. If you look carefully at the cap which she wears you can see a wing stretching over the hair; and at the front, over the forehead, is the head of a vulture. Only goddesses wear this vulture cap. Royal women are depicted with a cobra on their brow, which is called a uraeus and effectively protects, as well as identifies the subject as royalty. The style of dress that she wears is typical of those found in Dynasty 20, when the scene was painted, rather than the period when Ahmose Nefertari actually lived. Her hair is braided and held in position by what appear to be gold thread or beads at the ends. This is, of course, common in many African societies and amongst the African Diaspora. The bulk and proportions of the hair that is represented here also suggests that its type is African.

But what about the colour of her skin?

Here, I am going to suggest that the colour is symbolic rather than simply a realistic representation of Ahmose’s skin colour. In the same way that on Old Kingdom and Middle Kingdom statuary and statuettes women are often depicted with very pale and white skin. This does NOT reflect their true complexions. In fact this suggestion by Eurocentrics makes no sense at all, particularly when we consider that the consorts or male equivalents have the more typical dark brown skin colours, which is no doubt closer to that of the population at the time. I suggest this because by the New Kingdom both men and women are depicted with the same range of complexions.

By suggesting that white = racialised White then this means that women were of non-African descent but the men were! Of course this is completely ludicrous. I would imagine that Ahmose Nefertari’s skin colour was similar to that of her son’s, who is depicted with brown skin, and who also clearly has African type hair.

There are other posthumous representations of Ahmose Nefertari that show her with black skin. There is also a statue that now has a dark blue appearance, due to the original black pigment having been damaged by light. Using this powerful and potent colour to represent a goddess makes reference to her fertility and rebirth, which is why she was a popular goddess in tombs that were made substantially later than her lifetime.

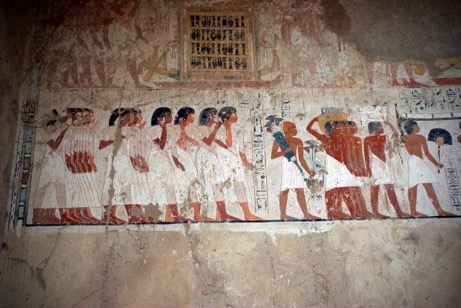

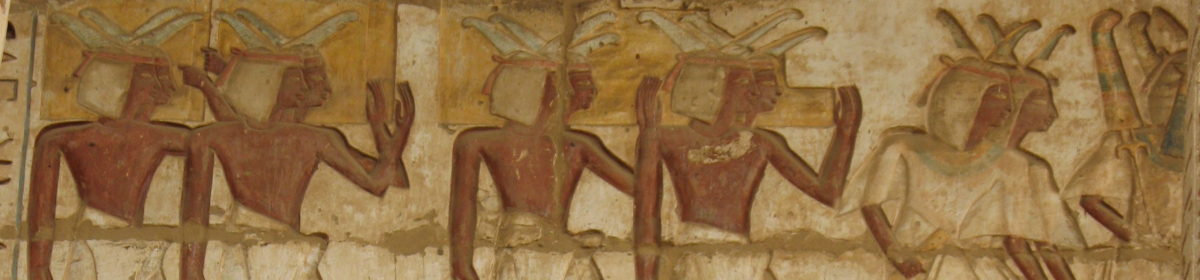

I find that when people start to explore ‘Egypt’ in its African context (Kemet) they focus on the more obvious references to people of African descent. The paintings of Ahmose Nefertari are a case in point. However, as their knowledge expands, they find that ALL aspects of this complex ancient culture are African and it makes no sense to try and remove it from other traditional African cultures. The complexions that depict mortals, as opposed to gods or the deceased, show them with a range of brown-coloured skins (below), as you find amongst people of indigenous African descent people today. It is these depictions that are probably a truer representation of the people of Kemet and also Kush. But let’s not forget what an advanced and complex society Kemet was, nor how this is demonstrated by their development and use of symbolism.

I would like to thank Dr Runoko Rashidi for inspiring this post. The views expressed are my own.

“By suggesting that white = racialised White then this means that women were of non-African descent but the men were! Of course this is completely ludicrous. I would imagine that Ahmose Nefertari’s skin colour was similar to that of her son’s, who is depicted with brown skin, and who also clearly has African type hair.”

– reply – for thousands of years people from the middle east sailed to Britain and Ireland to kidnap white slaves as they were considered beautiful – in viking times the Norwegians actually built Dublin as a slave port and would sell captures natives to traders that had sailed from modern day Lebanon – just as the ancient Minoan peoples are pictured as white and have been shown to have European dna and not Africa – and that was 5000 years ago – would you not then agree it is not ludicrous at all to suppose women had been bought, captured or out of their own free will ended up somehow in Egypt – I am not saying they were but to call it ludicrous is not a reflection of what could have been possible

wonderful post though thankyou for sharing

kind regards

It think it is not just the black skin but also the gold accents that are the combination of representing divinity. Not only do you see it with Ahmose-Nefertari but also with Bastet (gold accents), and at least one artifact of Ausar (one with gold eyelids), and also with the jet black depictions of Tutankhamun. This may be the direct influence of the black Madonnas in Europe who were not only jet black but with gold accents. I should think the Book of Dead depiction of Maiherpri was not necessarily a deity one but skin color.

Thanks for referencing Maiherpri. For me the pigment on the papyrus is a very dark brown and is typical of one of the many shades that we find on depictions of the people of Kemet. Interestingly, because of the darker shade Maiherpri is often referred to as a ‘Nubian’, which again comes back to this problematic issue of people labelling anyone who fits with their impression of an African person as Nubian rather than Egyptian. His hair style however is found on depictions of people with lighter skin, as we would expect because of the range of complexions that people of African heritage have. However, these people are ‘accepted’ as Kemites. I discuss this issue in more detail in another post: https://kemetexpert.com/egypt-in-africa/

Gold was typically associated with Kush and the Kushite people, hence Kushite people bring gold as an offering on tomb scenes and are also depicted with large gold earings. It was also associated with royalty and as you point out, divinity.

I think the wood sculptures are truer to skin tones than wall depictions. But even in wood, you can see ochre red and yellow in some depictions which can further explain red and yellow in wall depictions. In wood, however, everyone is an obvious brown – men and women – of varying shades.

Interestingly wooden statues were often covered in a plaster base and were then painted, including the skin colour. You can see this most commonly on the small wooden tomb model figures from the Middle Kingdom. Many of the existing statuettes have lost this outer plaster and paint coating, but if you look carefully at any splits in the surface of the wood you can see the white plaster base. On some examples you would need a microscope.

Yes, that’s right! I forgot. Like the bald bust of Tut from the lotus flower in which you can see several layers of coloring in the sections that are peeled.

I was also thinking of the tribute bearer from the tomb of Niankhpepi when the figure appears reddish brown on the skin, but you can see the red dripping and only partially covering with red the black hair. Instead of a perfected depiction, the artist may have deliberately attempted to show the imperfection of ochre red covering that occurred naturally.

I saw a documentary clip that had been passed around the internet a few years ago. I do not recall the name of it but I believe the segment featured the Samburu. Someone had remarked that they loved the reddish skin tone of the people. I took a closer look and responded that they were wearing ochre. I could see it because the babies had more of it than the adults and some older women more than younger and one of the co-hosts of the clip was in Western clothes visiting his own ethnic group and he had none and he was brown without the red. All the scenes were outdoors so it made sense they were covering their skin. Not to the extent of the Himba but it was there in varying shades.

And also remember Deidra, that the pigment of many objects has faded due to exposure to light. This is true of those outside and also museum items. It is only relatively recently that museums have begun to control light levels in galleries. And some still don’t have the means to do this. Even regular daylight alters the original pigments.

Understood!

: )

Why are we hated as a people ?? Is it Fear ??

That’s a very good question Nicole. And I think it is a good question for my next post. So I will share my thoughts via that over the next couple of days. Thank you!

It certainly is fear. In Apartheid South Africa 🇿🇦 there was a term created by the oppressive settler regime; DIE SWART GEVAAR (THE BLACK DANGER in Afrikaans). They used this term alongside many other myths about us to instill a high level of fear in the white population so they wouldn’t dare explore the facts for themselves.

Melanin is the Key to Our Greatness. Black Matter Paradigm. What was their view of this essential Hormone?

Melanin isn’t written about, but to some extent we can gauge their attitudes from how they represent themselves. We find people including royalty, noblemen and women, and workers depicted with different complexions.

It is so sad that we still have to clarify that the Egyptains were black African people. How much evidence is enough?

That’s a very good point and valid question. It shouldn’t be necessary to have to state that Kemet is African; but worse than that, this interpretation seems to still need to be defended in a way that a Eurocentric view was and still is often simply ‘accepted’.