The ‘Black’ Pharaohs

On the one hand mainstream Egyptology does not like to enter into discussions about the racialised identity of the ancient people; and yet certain representations are seen to be ‘acceptable’ as ‘African’. Dynasty 25 is a case in point. As rulers of Kush and Kemet these kings are often referred to as ‘The Black Pharaohs’ by the popular press and academics alike.

In 1999 Robert Morkot published an academic book: The Black Pharaohs. Egypt’s Nubian Rulers. Then in 2007 a book entitled: The Nubian Pharaohs. Black Kings on the Nile was published by Charles Bonnet and Dominique Valbelle. It detailed the discovery of the group of statues now in the Kerma Museum (above).

I’d like to spend a moment deconstructing these titles and thinking about the implications for African centred approaches within Egyptology. Both books use the term Nubian to distinguish these rulers from any other Egyptian kings. A future post will consider this term in more detail, but my point at present is that both titles infer that there was an artificial point beyond which people were indigenous Africans, and that anyone further north was not.

For me, part of the problem lies in exactly how Egyptology defines indigenous African peoples. By adopting the stance of deciding what is and is not ‘acceptable’ as an African we are simply seeing a continuation of those early attempts to deny that Ancient Egypt was an African culture that I summarised in an earlier post.

Who’s Black and who’s not?

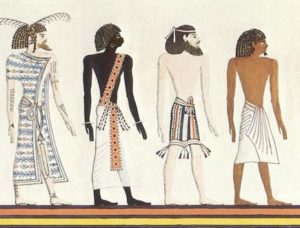

In that post I explored the racist ideologies of Nott and Glidden, who used the figure above to illustrate racial types. Three out of the four figures above are, of course, African. However, which would we identify in the modern sense of the word as ‘Black’. For many people who are of non-African descent, skin colour alone would be the deciding factor. Some people would fail to take account of other physical features, for example hair type, when considering this point. The Libyan, Nubian and Egyptian all have African-type hair and yet they are someone seen to be different. Libyans are generally depicted by Egyptians artists as having light brown skin; the Egyptians themselves range between light and dark brown skin tone; and of course the Nubians (Kushites) are depicted with jet black skin.

This is partly because many people fail to see the variation amongst indigenous African populations. It is because of this mindset that we find the Ancient Egyptian population being described as ‘mediterranean’ or ‘mixed’. It is worth noting that the term ‘mixed’ in this context does not refer to the diversity of African peoples, it is used to suggest that the entire population was in part descended from non-Africans.

Occasionally Egyptologists did identify some representations being of Africans based on features alone. When George Reisner discovered the representation of a woman at Giza, now in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, he described her as a ‘negroid princess’. Not a term that we would use today; but in a modern sense she was ‘Black’. So what makes some representations ‘acceptable’ as representations of Africans and others not?

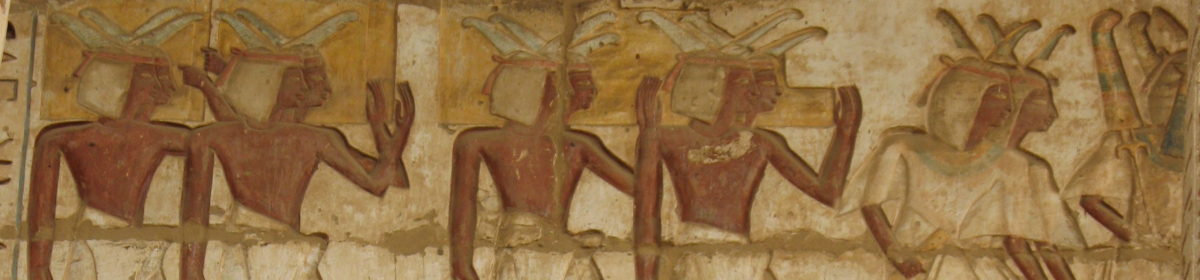

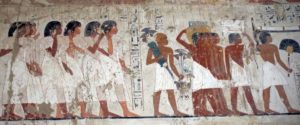

I have spent some years trying to answer this question. For me the range of skin tones and hair types that we see when Kemites represent themselves (above) reflects a range of indigenous African peoples. Over time, as the country was occupied by people from outside then there is a wider variety in the population and also the dominant culture. A timeline of foreign contact illustrates this point well.

People who are from specific racialised groups are notoriously poor at recognising people who are from a different racialised background. This has consistently been found to be the case in eye witness identifications. This is probably because people focus more on the difference, for example skin colour, than other details. If we think again of the case of Ancient Egyptians, there are a number of factors that will influence whether someone identifies a representation as being of an African person:

- If someone believes that the Ancient Egyptian people were European, they already show a bias. I discussed confirmation bias in my last post.

- Some people do not understand the variety of skin colours and shades that are found amongst indigenous African people.

- The ancient representations of the people from Kush present one type of African person. However, it seems today that unless an image matches this ‘type’ then it is not deemed to be ‘African’.

A few points to consider

- Very few people of African descent have skin that is the colour of the Kushite representations. The ranges of skin tones of modern day indigenous African peoples are actually closer to those that we see on depictions of Kemites.

- Ancient Egyptian artists sometimes depicted people from Kush with the same skin colour as those from Kemet (see left).

- The hair type and hairstyles that are shown on Kushites are also found on depictions of Kemites.