The role of Ancient Egypt in theories of ‘race’.

Many academic disciplines in the nineteenth century were embedded within the racist ideologies of the societies and academies where they developed. This is true of the sciences and humanities, including Egyptology, which was directly linked to the study of ‘race’. However, before we go any further to exploring the relationship between racism and Egyptology, it is worth considering the following definitions.

- Race is a social construct that first appeared in the seventeenth century CE and it is biologically determined. It should not be confused with the term ethnicity.

- Ethnicity, which is defined as a category of people who identify with each other on the basis of shared ancestral, social, cultural or national experiences.

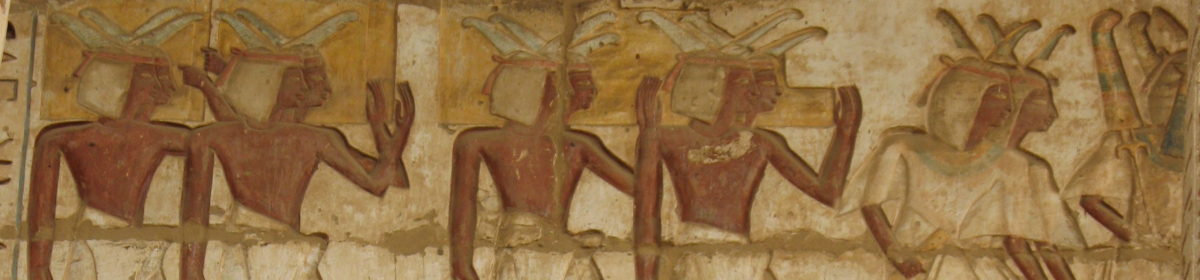

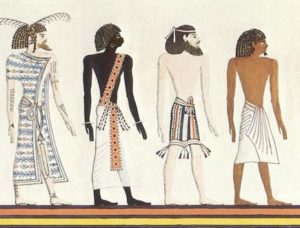

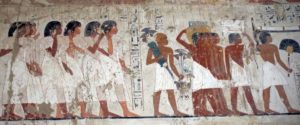

The drawing above appeared in the 1854 publication Types of Mankind by Josiah Clark Nott and George Robert Gliddon (1809-1857). It was taken from the Tomb of Seti I, where it was originally intended to show (from left to right) Libyan, Kushite, Asiatic and Egyptian/Kemite peoples. In their publications the pair copied the reliefs on Egyptian temples in order to claim that the ancient people were typically ‘Hellenic’ (of Greek descent), ‘Semitic’ and even ‘Jewish’.

Nott was an American physician and surgeon and he published on the theory of race. Gliddon was originally born in England but spent time in Alexandria, Egypt, which is possibly where he developed a fascination for the ancient culture. Both men were followers of the American physician Samuel George Morton, who advocated each ‘race’ of people had been created as a separate entity and were not from the same single source.

In 1844 Morton published a volume entitled Crania Aegyptiaca, for which he examined the remains of people from Kemet and concluded that they were not of African descent, but were somehow a “blend” of other races (p.4). A quick glance over the introduction instantly demonstrates how subjective and biased Morton was in his writing.

Racism and Egyptology

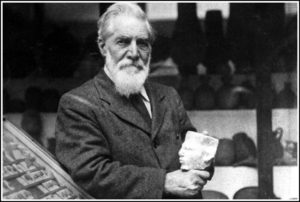

Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie was appointed the first professor of Egyptology in the UK in 1892 at University College London (UCL). He was a prolific excavator of sites in Egypt, and wrote many publications on his work. Also at UCL during this period was Sir Francis Galton and Karl Pearson who were both pioneers of the eugenics movement. In fact Galton actually coined the term ‘eugenics’; a word taken from two ancient Greek words meaning ‘well/good’ and ‘group/kin’). His ideas are captured in a book entitled Hereditary Genius, published in 1869, where Galton wrote the following:

Let us do what we can to encourage the multiplication of the races best fitted to invent, and conform to, a high and generous civilisation, and not, out of mistaken instinct of giving support to the weak, prevent the incoming of strong and hearty individuals.

Galton, Pearson and Petrie worked closely together. Petrie provided the Anthropomorphic Laboratory at UCL with human skulls from Egypt for study. Thus, once again the ancient culture was used to illustrate theories of race. However, this time it was also directly influencing the newer field of Egyptology. Today these ‘theories of race’ are deemed to be racist, but Petrie fully embraced them in his work.

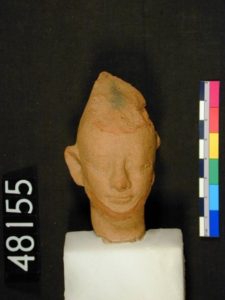

When I worked at the Petrie Museum as a research assistant, I was tasked with registering around 250 terracotta heads that had been collected by Petrie from the site of Memphis. Petrie became obsessed with identifying racial types, writing the following in 1909:

The discovery of portraits of the foreigners was not even thought of and only gradually was it realised that we had before us the figures of more than a dozen different races.

Such quotes show the extent to which Petrie was influenced by contemporary theories of race. If you are interested in further exploring the relationship between Petrie and Galton, it was the subject of a publication in 2013 by Debbie Challis entitled: The Archaeology of Race: The eugenic ideas of Francis Galton and Flinders Petrie. There are also a number of publications that were part of the Encounters with Ancient Egypt conference that critically explore how Egypt has been viewed in the past, and this includes a volume on Ancient Egypt in Africa.

How did the ancient people view themselves and others?

The ancient people of Kemet distinguished themselves in terms of their appearance and also their culture from their surrounding neighbours. It is worth noting that unlike the later European and North American theorists, these differences were not made solely on the grounds of physical appearance.

- Libyan people were typically distinguished by their light brown skin, shoulder lock of hair and their headdresses.

- Kushite people, from what is now Sudan, had black skin, short hair that was often coloured with henna and typically wore gold earrings, as a reference to their control of the gold mines.

- Asiatic people were the only non-Africans to be depicted, and came from the countries that would now be referred to as the Middle East. People from this region were generally shown with yellow skin (to identify them as being different to those who were African) and later in Roman period they were shown with pink coloured skin. They wore beards and were also depicted in clothes that were different to African peoples.

- Finally, Egyptian/Kemite people had a range of different skin colours from dark red to brown (see above) and were shown with many different types of clothing and hairstyles because artists depicted a greater range to represent their own people than for those who came from other cultures.

A final question

Given that the foundations of Egyptology are so closely connected to racist ideologies and theoretical frameworks, is there then, still evidence of this attitude within the discipline today? In my next few posts I will be highlighting how the remnants of past theories can permeate through to the present.