Jebel Barkal

Jebel Barkal means sacred mountain in Arabic. The fact that this large natural feature, which lies around 200 miles north of Khartoum, has been recognised for thousands of years is testimony to its power. Priests who accompanied the Kemite King Thutmose (I) Aakheperkare and his army, who entered Kush in 1504-03 BCE, identified the feature as “Pure Mountain” and “Thrones of the Two Lands”. These titles were a reference to the god Amun; the priests believed that this was the place where he lived.

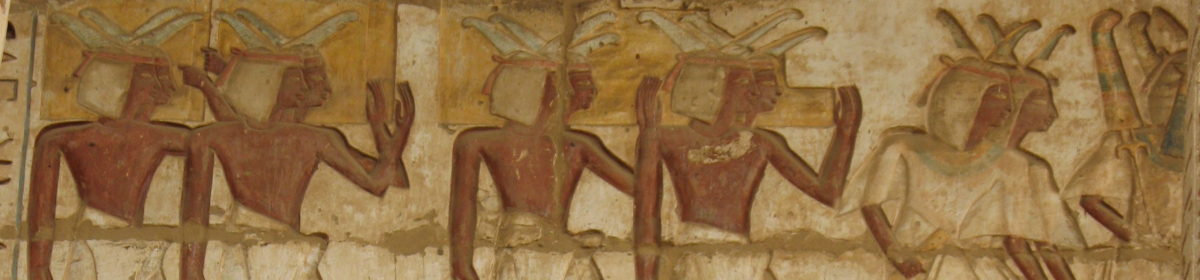

The ancient people were very responsive to their natural landscape. A temple, which was cut out of the mountain’s rock, offers a clue as to what prompted the priests to come to their conclusions. The ancient people saw the profile of a uraeus or cobra when they viewed the rock (above) and this was depicted on a relief representation inside temple B 300 (below). Here the cobra wears a sun-disk on its head.

To the right of the depiction of the mountain King Taharqo who also ruled Kemet (690-664 BCE) makes an offering to the gods Amun and Mut. The divine pair are represented in front of the the sacred mountain. You can just about make out the crown of Amun on the photograph above. The reliefs are badly damaged. Taharqo, who was also accompanied by his consort, can be seen below.

A sacred complex

The earliest sacred archaeological remains at the site date to the reign of the Kemite King Thutmose Menkheperre (usually referred to as Thutmose III) who ruled Kemet from 1479-1425 BCE. This king laid the foundations for the temple to Amun, which was later completed by Ramesses Usermaatre-setpenre, better known to us as Ramesses II (1279-1213 BCE). The early temple, which was constructed out of mud brick has been replaced by a succession of later buildings. The majority of those standing today date to the reigns of the Kushite rulers who formed Kemet’s Dynasty 25 (around 746-664 BCE).

Temples were positioned in front of the sacred mountain. Today, only scant remains can be found. The photo below shows the dromos (processional walkway) flagged on either side with statues of the god Amun in the form of a ram. The sandstone bricks on either side once formed part of the pylon (gateway).

Home of Amun

The reason that the Kemites were so interested in this site was because they believed that it was the dwelling place of Amun, a god who originated in Kush but who had one of the most powerful priesthoods in Kemet, and indeed one of the largest temple complexes at the site now known as Karnak (below).

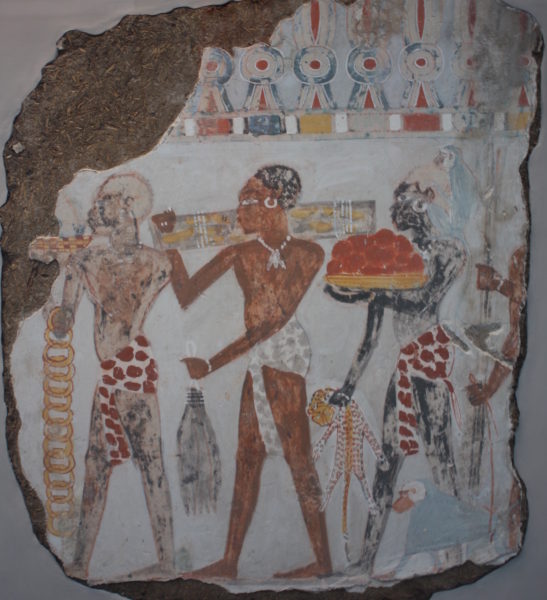

Both complexes had temples and shrines dedicated to other deities. At Jebel Barkal these included Hathor (below) and the Cobra goddess.

Continuity of a sacred space

When the Pure Mountain became known as the Sacred Mountain with the advent of Islam, the space retained its religious importance. Since the nineteenth century CE there has been a the tomb of a Sheikh and a Muslim cemetery at the site.

However, perhaps most importantly for the purposes of this blog, the site is evidence of the cultural connections between Kemet and Kush. Politically the two cultures were divided in ancient times. However, it is clear that the priests who accompanied Thutmose I recognised the site as one of the most important to their cult: the dwelling place of Amun.

The natural landscape also consistently played an important role in Kemite and Kushite religious practice, and this is common in other traditional African religions.