Further comments on ‘Black Pharaohs’ By Dr Shomarka Keita

The error of affirming the consequent must be acknowledged. Dislike has many causes.

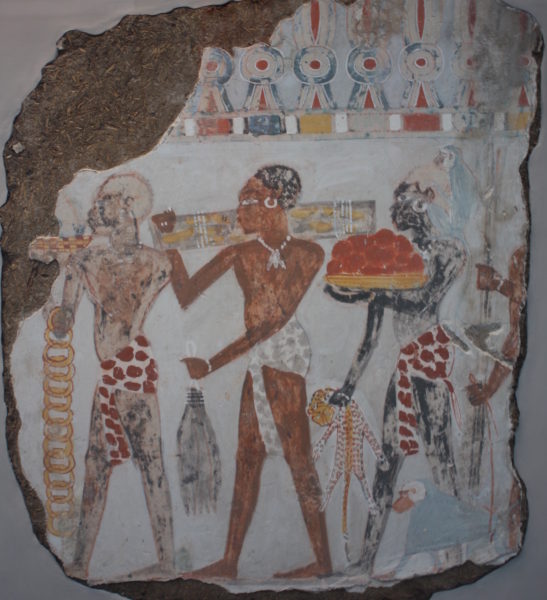

It can be argued that familial ties are stronger than all others even in difficult circumstances, and that when there is a conflict between family ties versus group ties that family pre-empts all. However, there are too many instances in the recent western experience where this is simply not the case. One example is that during the antebellum period in the USA, Euroamerican males routinely sold their children by enslaved [powerless] African and Afro-descendant women into slavery (how about that for a #metoo moment). (There were exceptions of course.) All of this is rooted in a notion of racism, specifically anti-“black” racism. This is mentioned since the PBS presentation “Black Pharaohs” expressed various interpretations in a “white”-“black” dichotomy that even European crusaders looking for allies in a black Prestor John would not have understood. Of course the televised piece is not the only place this has been done. There are books and magazine articles that speak of the “black” experience in Egypt which is problematic on various levels as stated before.

Details are interesting when one is discussing racism and interpreting the past in terms of it. It is not clear that those who invented racism as we understand it and then structured human society around it for their benefit fully understand it. Their various descendants participate in the world view generated by racialism (and/or racism) and perhaps maintain it but cannot be blamed for creating it: their bias may be unconcious, not deliberately theorized and operationalized but only by studying each situation can this be known. Racism in its visceral form as understood in the USA is not amenable to monetary or spiritual negotiation. This will influence how many interpret a situation of conflict.

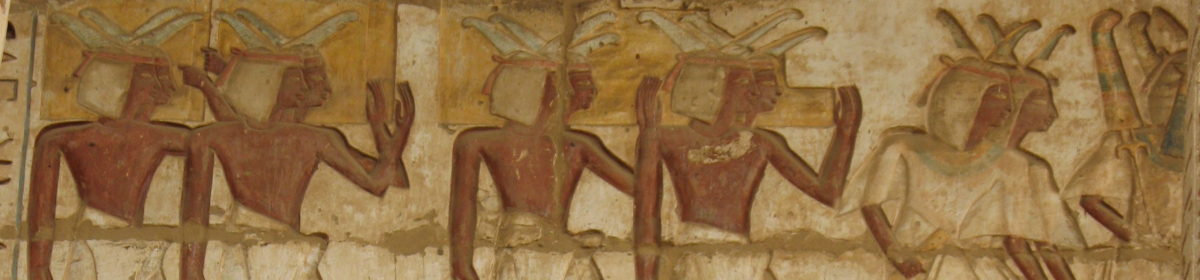

An idiographic approach to the question of Egyptian shame about being associated with Kushites might be useful. Let us drill down on something that would have been personal but also public, on the “national” stage. We note that in her tomb chapel Piankhi’s daughter, Amenirdis, was installed as “God’s Wife” of Amun (an important title) by being adopted by her non-Kushite predecessor, the usual way this was done. Her name and images are intact and obvious. Only Pharaoh Piankhi’s cartouche has been removed. The 26th dynasty’s king’s daughter was in turn adopted by the last of the Kushite “Gods’ Wives” and thus there was seamless succession in this role. If there was shame at being associated with or ruled by specific folk with darker skin at the family level—assuming this to be the case— or folk usually associated with darker skin at the group level, then how could this seamless transition have occurred between Kushite and others? There is no evidence of shame here. There is no hiding this succession. There is no apparent conceptualization that there is taint associated with taking on the Kushite as successor, and then receiving from a Kushite the same honor via adoption—which in theory should be more susceptible to prejudice than having to deal with actual kin.

The damnato memorae was directed at a king over what is more plausibly interpreted as some personal angst than an attitude about a group based on color. Of course there are other possible explanations that have to do with the cultural intricacies and etiquette of those times that we will possibly never know.

The error of affirming the consequent must be acknowledged. Dislike has many causes.