Curating Kemet

There are a number of very simple approaches that museums could utilise in order to reaffirm the African origins of Ancient Egypt. And if you find yourself in a position to impart knowledge to others and are tired of waiting for this to be be implemented in your local museum, you can, of course, quite easily do this yourself.

1. What’s in a name?

A simple technique that I used when writing the information for a virtual gallery was to refer to anything that dated before the Ptolemaic Period (332 BCE) as ‘Kemet’ rather than ‘Egypt’. Αίγυπτος/Aegyptus were the names used by the Ancient Greek and Roman writers for Kemet. By continuing to use it, we are effectively still looking at the culture through a European lens. By abandoning this name, it is also possible to remove many of the Eurocentric interpretations that have been place upon this ancient African culture. It encourages people to look at the culture from a fresh perspective.

Many of the names that we use for rulers of Kemet are Hellenised (from the Greek versions). For example, Senusret Kakaure (left) a ruler of what we now refer to as the Twelfth Dynasty is sometimes referred to as Sesotris, which is the Greek version of his name. A similar issue arising the the use of Arabic names for ancient sites; Tell el-Amarna/Amarna, was named Akhet-Aten when it was occupied by the ancient people. By using the original African names we immediately resituate the ancient culture and its people.

A helpful site that lists all of the original names for the kings of Egypt and also gives the original names for sites is Digital Egypt.

2. Cultural context

When an object is removed from its original site, the context is lost. It is therefore essential that museums seek to present objects within the appropriate cultural context. In university and national museums in the UK the Ancient Egyptian galleries are rarely connected to other African cultures. One exception to this is the Africa gallery at the Horniman Museum in south London. Here, a Kemite coffin is displayed alongside more recent ethnographic materials (see below) from a number of cultures from Africa and the African Diaspora.

Kemite culture has much in common with other African cultures: from individual items such as hair combs, pottery, basketry, headrests; to concepts such as traditional religions, kingship and the role of women in societies. By referencing other African cultures that we know more about, curators can help visitors to obtain a better understanding of an ancient culture. In spite of this observation, you are more likely to find the Kemet collections next to the galleries that display Ancient Greece, Rome and the Ancient Near East than the African galleries. Adding ‘Africa’ to the name of a gallery that relates to ‘Ancient Egypt’ would be a good starting for many museums.

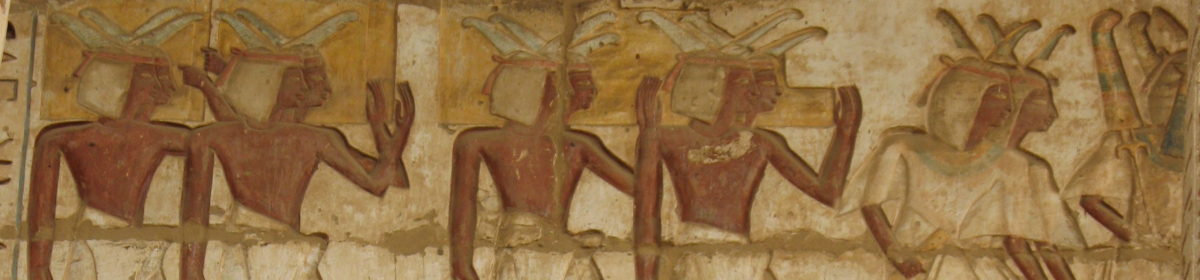

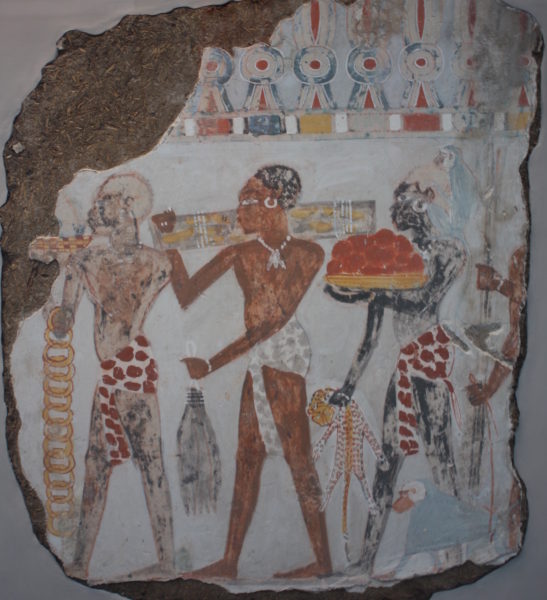

3. Illustrations

Illustrations and reconstructions are an important part of the presentation of cultures in museums, particularly when that culture is ancient. The photograph on the left shows a display in the Kerma Museum, Sudan and offers a powerful artistic interpretation to illustrate how the original owners of the grave goods would have worn these objects. The racialised identity of such reconstructions is important, because at an unconscious level we are likely to recall this when we think about the culture and its people in the future. Many people who have attended talks that I have given on Kemet have later said that they had simply never thought of Ancient Egypt as African. This is, in my opinion, largely the result of the media (for example films or documentaries that show reconstructions of the ancient people), museums, and the education system failing to differentiate between the ancient and more recent cultures in Egypt.

4. Historical timeline

Which brings me onto the fourth point: looking at this region’s historical timeline and acknowledging the changes in cultures and populations that have occurred over the past ten thousand years. I have summarised the key periods in a previous post under the heading From Kemet to Egypt to Misr. By recognising external cultural interactions and internal transitions, it is possible to obtain a better understanding of Kemet’s importance as an ancient indigenous African culture. Historical timelines also demonstrate the importance of this region and its people in the development of the Coptic church, and so Christianity more widely.

5. Connecting with Kush

In two recent posts I have observed that museums often differentiate between the people and cultures of Kemet and Kush. The result of this practice is that any representation from Kemet that is seen to represent an indigenous African person will be labelled as ‘Nubian‘. This practice continues to be standard, in spite of the fact that the majority of museums acknowledge the similarities between these two ancient cultures.