A case of cognitive dissonance?

Sometimes people hold a core belief that is very strong. When they are presented with evidence that works against that belief, the new evidence cannot be accepted. It would create a feeling that is extremely uncomfortable, called cognitive dissonance. And because it is so important to protect the core belief, they will rationalize, ignore and even deny anything that doesn’t fit in with the core belief.

Frantz Fanon Black Skin, White Masks 1952

The Theory of Cognitive Dissonance was further developed by American psychologist Leon Festinger and published in 1957. Festinger suggested that we all strive to maintain consistency in our attitudes, beliefs and behaviours. That when there is an inconsistency we find this unpleasant and fall into a state of cognitive dissonance. In order to correct this tension we will automatically try to reduce or eliminate the inconsistencies. One way to do this is, as Fanon observed, to deny any evidence that does not fit with our existing belief or opinion.

Confirmation bias

We also know from experiments that people preference information that confirms an existing belief. This is known as confirmation bias and is the tendency to search, interpret and recall information that confirms a belief that we already hold. Of course academic work relies on evidence to support or dismiss theoretical interpretations. The problem when dealing with an ancient culture that no longer exists in its original form is that the evidence upon which we base our knowledge is extremely limited. Furthermore, we are influenced by our own identity, our view of the world, and how we learned about that culture. These issues can be magnified if that culture is studied in isolation, as is often the case with Egyptology.

Interpreting Ancient Egypt

I am often asked by people of both African and European descent why I view Ancient Egypt as an African culture. The inference being that as a White academic I must have a personal reason for choosing to undertake research from an African-focused perspective.

The answer is pretty simple. I view Egypt as African because this was how the ancient culture was first introduced to me: through the eyes of Greek and Roman artists, philosophers and writers. And more recently my work on other African cultures has presented further evidence that an African framework is the most sensible one in which to view Ancient Egypt prior to the first millennium BCE.

I am certainly not unique amongst UK Egyptologists in seeing Ancient Egypt this way. A number of museums in the England promote Ancient Egypt as African in terms of its geography, and its indigenous population and culture. The World Museum, which is part of the National Museums Liverpool, used an actor of African descent to play the part of a King in its educational films (see above). As I write, their Egyptian galleries are currently closed for renovation. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian and Sudanese Archaeology in London regularly holds events that explore Ancient Egypt alongside other African cultures. And the Fitzwilliam Museum has a dedicated on-line Virtual Kemet Gallery that I developed during my time there as a curator, as part of community-focused project.

From Kemet to Egypt to Misr

Looking at a basic timeline demonstrates the extent to which the population and culture of Kemet have changed over the past 5000 years. I use this time span because it includes the first identifiable cultures known as Pre-Dynastic through to the present day. In addition to trading with other cultures from early in its history, Kemet was also ruled by outside cultures. The earliest of these were the Hyksos (known by the Kemites as ‘rulers of foreign lands’) during Dynasty 13 (around 1700-1550 BCE). Culturally the Hyksos derived from the Palestinian Middle Bronze Age.

From the first millennium BCE, Kemet was ruled by a number of out cultures, two of which were also African:

- Libyan– Dynasty 23 (818-715 BCE)

- Kushite– Dynasty 25 (747-656 BCE)

Then from 525 BCE non-African rulers controlled Kemet, which became known as Egypt under the Macedonians and Ptolemaic rulers. Then in 642 CE Egypt became the Arabic Misr.

-

- Achaemenid Iranian (525-404 BCE)

- Second Persian (343-332 BCE)

- Macedonian and Ptolemaic* (332-330 BCE)

- Roman (30 BCE-395 CE)

- Byzantine (395-668 CE)

- Islamic Period (642 CE)

*During the traditional periods of its history the Ptolemaic dynasty was the only non-indigenous to be resident. The other cultures continued to rule Egypt from their own states.

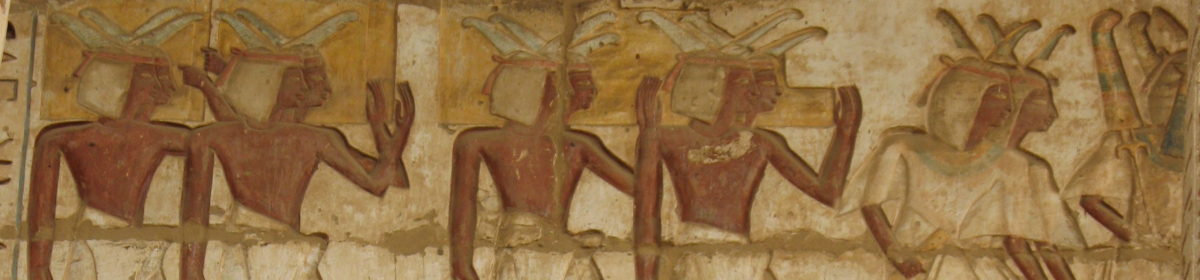

Remarkably the culture of Kemet continued in its traditional form until its population changed their religion. The Egyptian script continued to be used in religious contexts during the Ptolemaic and Roman occupations, in spite of the ‘official language’ changing to Greek. And Ptolemaic and Roman rulers were depicted on temple reliefs performing their duties as rulers of Egypt (see above).

Then, as more and more people began to convert to Christianity, the original religion and culture also began to change; temples were abandoned and there was no resident ruler to fulfil the religious or societal role of King. With the advent of the Islamic settlement in Egypt, around 642 CE, the culture, language and religion changed entirely. The new settlers often made reference to the past in their writings and architecture. The minaret of the Ibn Tulun mosque (above), and which dates to the ninth century CE was modelled on the famous Pharos Lighthouse of Alexandria, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

Avoiding confirmation bias

The history of Kemet/Egypt/Misr spans well over 5000 years. If, when looking at this vast timespan, we limit ourselves to a single approach, and we fail to acknowledge the impact of outside cultural influences upon the indigenous, then we automatically limit the evidence base that we are able to utilise. If we also consider the origins of egyptology as a discipline then the potential for a biased viewpoint is further increased.

Greetings to all historian I love history with my whole heart because it is the light in the time of darkness it is time where the whole world needs the reality it is my wish that those who knows the history come together and inlighten the world that is in the great great darkness

Gulwa D Sent from

hello,

I’m just starting to study about Kemet. I had no idea until just a few month ago

how much true history was there. I am trying to find as much about Kemet and it’s

people as I can. For quit some time I knew that christianity had something wrong

with it but, until the last few months I realize just how much bunk in in it.

maybe you can give a few hints where to look for more info and maybe some

videos I’m trying to learn as much as I can.

Thank you for any help you can give me.

Sincerely,

Vince Wharton

ps this is my first coment

Look up:

– Dr John Henry Clarke

– Dr Yocef Ben Yochanan

– Dr Ray Haggins

Chancellor Williams

Dr. Anthony Browder

Dr. Van Sertima

9 World Chronicles

Khemetic Centered Living

Hidden History of the Nile Valley

Dr. Runoko Rashidi

Dr. Ashra Kwesi

Maat Forever

Dr. Anthony Browder

Dr. Van Sertima

9 World Chronicles

Khemetic Centered Living

Hidden History of the Nile Valley

Dr. Runoko Rashidi

Dr. Ashra Kwesi

Maat Forever