Combs from Kemet (and Ghana)

I spent the best part of 3 years researching African hair combs. And just when I thought that I knew everything there was to know and had found every possible parallel for the combs from Ancient Egypt, I came accross a number of very interesting combs in the National Museum in Accra, Ghana (below).

The objects above were excavated by a British archaeologist Thurston Shaw at the site of Dawu. The rubbish dump where they were found was dated to between the mid-seventeenth and eighteenth centuries CE. This coincided with the time that the town was absorbed into the Akwapim Empire. The comb on the left is important because it is almost identical to the combs that were made by African people who had been enslaved and transported to the US. The comb, or decorative piece, in the middle on the right, struck me because it is almost identical to a comb that is housed in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. The difference being that the Cambridge comb (below) is around 6000 years old and from Kemet.

It isn’t possible to say that two combs that are 6000 years apart are directly connected. We can only make this assumption if we can show continuity through time. However, until I saw the Dawu comb I had failed to find any parallels for the comb above apart from those in Ancient Egypt. It is possible that the two combs were used as decoration for the hair, or that they served a particular purpose in styling.

A better understanding

By looking for parallels within other African cultures we are able to obtain a better understanding of how items that relate to hair were used in Kemet. Ethnographic photographs from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries show that combs were used for multiple purposes. This includes combs being used as status symbols, as decoration for the hair, and as tools; which accords with the evidence from Ancient Egyptian burials. There are also parallels in the decorative techniques that were used in both Kemet and West African cultures. The incised circular decoration on the teeth of the Dawu comb (below right) was also used in Ancient Egypt.

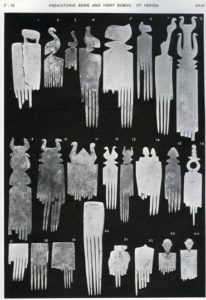

A good reminder of the variety of different types of comb used for African type hair

I started this post with an image that I took when the Origins of the Afro comb exhibition was on. Being a curator allows you to display objects that you have always wanted to see together and which are not typically shown in that way. For me one of the most exciting things about curating that exhibition was being able to display a 1970s Black power comb next to an Ancient Egyptian comb that was found in a grave at the cemetery of Abydos.

- In Predynastic Kemet, combs were used as a status symbol and were also worn in the hair. This is a common practice in other African cultures.

- The earliest combs were in the form of a ‘pik’.

- The symbols on the handle are often in the form of an animal or part of an animal; perhaps suggesting a religious or power connection.

Once again we can’t make a direct connection between the two combs above, but in terms of their form they are the same. And it is worth noting that we do not find this type of hair pik in any ancient cultures outside of Africa. Even William Matthew Flinders Petrie, who I mentioned in a previous post, noted that there were no European parallels for this form of comb. He wrote the following in his 1927 publication Objects of Daily Use:

The early European combs, of bronze age and onward, differ entirely from the Egyptian examples, being always single edged and run backed

Combs with shorter teeth

I was pleased to be reminded, by the Dawu combs, that many African combs are not in the form of a ‘pik’. Of course combs with longer teeth are only appropriate for specific styles of hair and in the same way that not everyone with African type hair uses a ‘pik’ today, the same is true of earlier periods.

From around 4000 years ago the form of comb illustrated above was commonly used in Ancient Egypt. The main difference between those from Kemet and ancient European combs is the width of the gaps between the teeth. Those from Africa tend to have more space, presumably because the users and makers of combs were aware that African type hair can be fragile and prone to breakage.

*Please share your thoughts and comments below*

Were the combs only used by people of higher class or commonly used by most of the people in ancient Egypt?

In short, we don’t know. They are only found in elite graves, but people from lower social classes used a wide variety of objects and items during their lifetimes that were not buried with them. The graves with the combs in the Pre-Dynastic period at cemeteries were found in rich graves, containing a range of higher status objects.

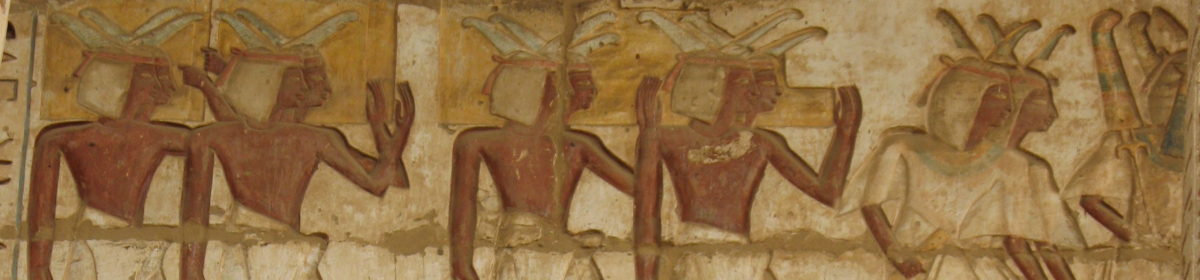

Im going to go a step further and say that I dont think the AEs wore head dresses, nemes, crowns or whatever they are called. I believe that they had their hair shaved into those shapes. They all had braided hair. Look up King Tuts mask in 360′ view. Those are braids not a headdress.

Thank you for your exhibition and this website. Because of your work and your recent finding, I have another piece linking Kemet (Ancient Egypt) to the rest of Black Africa. Curators are scholars too, and you sir, need to publish these findings so the world can begin to acknowledge you for generations to come!

Thank you for your comments and words of encouragement. I’ve made my last publication available as a pdf: https://www.academia.edu/15470261/African_Hair_Combs

One of the most drastic examples of AE and SSA cultural overlap that doesn’t necessarily translate to genetic closeness are the Afrocombs found in many neolithic Egyptian sites. While Afro textured hair was definitely present, this wasn’t the predominant hair type. Examination of AE hair as early as the predynastic shows a tendency towards cross sections with oval shapes, not flattened, elliptical shapes characteristic of the Afro-textured hair most people associate with afrocombs.

There are so few examples of hair from this period that I, personally, wouldn’t generalise across the population. It’s worth noting the variety of hair types amongst African people.

True re the variety of African hair. When it comes to the Nile Valley, there seems to be this huge attempt by people who support an African origin of AE, to try to force theyre hair into a range where some of it clearly does not belong. Instead of raising the bar of what African hair is capable of expressing, they rather try to force Egyptian and Nubian hair into the old stereotyped construct, just to be on the safe side. Some people here also seem to drool over Herodotus’ description of AE hair, as whooly, which is only partly supported by examinations of mummy hair.

“Some people here also seem to drool over Herodotus’ description of AE hair, as whooly (sic), which is only partly supported by examinations of mummy hair.”

I checked over the comments on this blog to find instances of where people here “drool” over the Herodotus quote on woolly hair. I may have missed them, but I couldn’t find any.

The only reference I could see is the one provided by Dr Ashton:

“Many readers will be familiar with another quote from Herodotus (Histories 2:104) that makes reference to the appearance of the people of Kemet having dark skin (melanchroes) and curly (often translated as ‘woolly‘ on account of the word ‘oleos’. “

https://kemetexpert.com/2016/05/

There is a multitude of portrayals that supports the Afro hair texture. Africa has the most genetically diverse population on the planet. Of course this genetic diversity is present within the hair styles and textures. Women of East African descent tend to have straighter hair than those from different areas of the continent. The hairstyles that we see present are a representation of the styles wore by the indigenous populations. Braiding, Afros, etc were all present as they are to this day. So there should be no surprise as to why we are seeing Afro combs coming out of the Nile Valley.

There seems to be a small attempt by those who where educated in eurocentric ideas and beliefs to never realize what they have been taught and hold dear and true, is a lie. However, many people here would drool over my Master’s degree project, ‘The Africanness of Ancient Egypt.’ Of which I successfully defended thereby attaining my first masters in African Studies from Ohio University class of 2015.

Well said.

I still galls me that Eurocentrists, particularly the largest population emanating from United States, still deny the obvious truth with their last breath.

Good work. Keep it up.

Thank you!