Dr Vanessa Davies is the founding organizer of a new initiative named The Nile Valley Collective , here she shares her research and thoughts on the divide between Egyptology and Africana Studies.

There needs to be a marriage between Egyptology and Africana studies

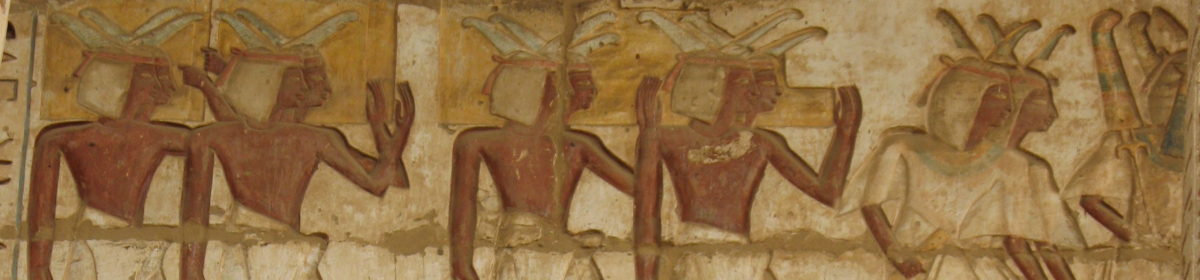

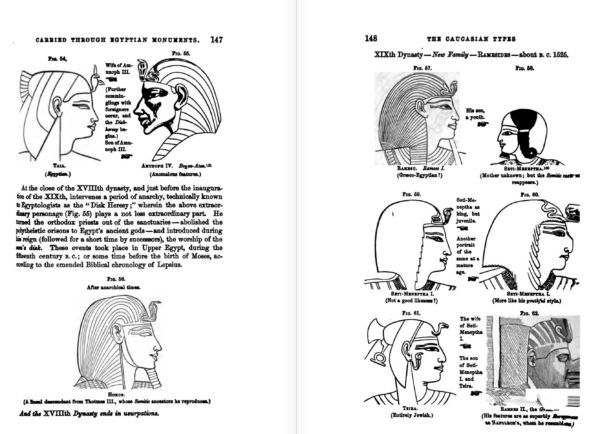

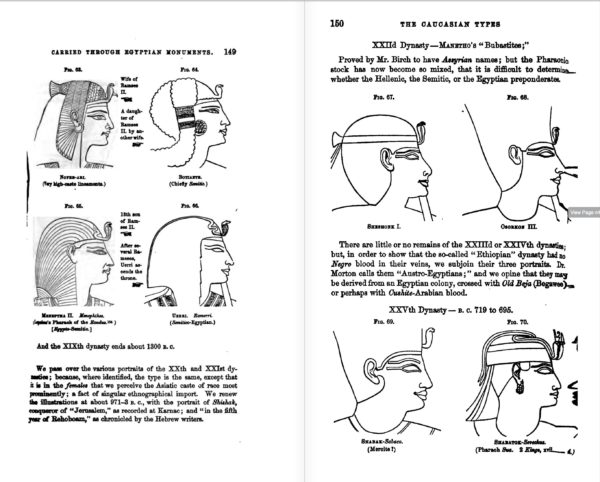

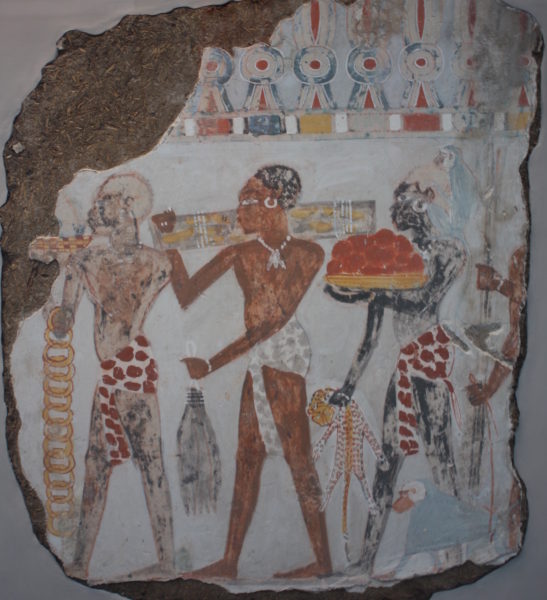

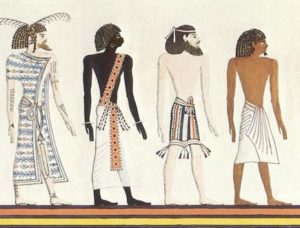

In the US, there is a divide within the university system between white Egyptology and Africana studies. By white Egyptology, I mean the Egyptology programs in the US, which are largely staffed by white people, whose research questions and interests trickle into mainstream popular culture via television shows. I use this phrase “white Egyptology” out of respect for the people who work on Egypt and Nubia through the lens of Africana studies. In the US, most scholars of Egyptology are white. Most scholars of Africana studies are Black. This racial and scholarly divide reflects unstated or understated racisms that have underpinned white Egyptology since its inception in the US as part of the university curriculum. This divide must be bridged.Egyptology as a research discipline was established by white European, and later American, scholars to address the questions and perspectives that interested white audiences, scholarly and popular. The two earliest professors of Egyptology in the US, both white men, received their appointments at the turn of the twentieth century. Their graduate education in Germany and in the US was rooted in Semitic languages and cultures and followed Eurocentric interests of that time in looking for connections between ancient Egypt and the stories in the Bible. They separated Egypt from Africa.

As time went on, scholars of African descent studied Egyptology and engaged with white Egyptologists: W. E. B. Du Bois, Leo Hansberry, Cheikh Anta Diop, and Theophile Obenga, just to name a few. These scholars brought new perspectives and new research questions to white Egyptology. But they were ignored or pushed away from it.

Spurred by the civil rights movement, universities in the US began establishing departments in the 1960s and ‘70s that were dedicated to the history and culture of Africa and the African diaspora. The establishment of those departments was vital to correct the false and dehumanizing claim prevalent in the US that Africa had no history and that by extension African-Americans and Africans elsewhere in the world did not share in the human experience of history.

With a few exceptions, as Africana studies grew and flourished, it did so largely without contact with white Egyptology. White Egyptology, as it moved from solely a graduate program to being a small part of the undergraduate curriculum, did so largely without contact with Africana studies.

This unfortunate divide reflects the longstanding and incorrect separation of ancient Egyptian culture, and to a lesser extent ancient Nubian culture, from its African context. White Egyptology programs in the US are typically found in departments centered on the Near East (the term denoting the ancient cultures of Mesopotamia, the Levant, and related zones).

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, most white Egyptologists had no knowledge of the other ancient cultures in Africa. Their ignorance about the wider cultural context of Africa and about connections between Nile Valley and other African cultures has largely been perpetuated with each subsequent generation of Egyptologists.

I received my Ph.D. from the University of Chicago. Besides one class on ancient Nubia and one on art historical theory, all my coursework was focused on Egypt. For language study, one could take Egyptian and Near Eastern languages, such as Akkadian or Sumerian, or Arabic, but there were no offerings on other ancient languages of Africa, such as Berber or Meroitic.

Imagine the fruitful work that white and Black Egyptologists could do if they were placed within Africana studies departments. Imagine the dialogue that could take place about ancient African cultures, the explorations of the widespread reception of ancient Egypt and Nubia in myriad cultural expressions over the decades.

W. E. B. Du Bois understood the race divide in academic pursuits (Davies, 2020). He wrote the histories of African people because he knew that to omit them is “scientifically unsound and also dangerous for logical social conclusions.”(Du Bois, 1946: vii): Yet, despite the fact that he read widely on Egyptology and published on Nile River Valley history, he wrote this disclaimer in his 1939 preface to Black Folk, Then and Now, “I am no Egyptologist. That goes without saying.” He then proceeded to describe exactly what ideas and which Egyptologists he disputes. A few years later, when he published The World and Africa, his description of the Egyptologists he engages with reads like a who’s who of the field at that time. At what point does Du Bois “get” to become an Egyptologist? The same question must be asked about Leo Hansberry, the African-American professor never recognized by white Egyptology, whom Du Bois described as “the one modern scholar who has tried to study the Negro in Egypt and Ethiopia [i.e., Sudan]”(Du Bois, 1946: x).

The divide between white Egyptology and Africana studies must be bridged to open up Egyptology and to make it more inclusive. Going forward, Egyptologists must be better versed in other ancient cultures of Africa, must dialogue with communities of color, must understand the questions and viewpoints that abound in Africana studies, and must respect the reception of these ancient cultures by people of African descent today.

The divide between white Egyptology and Africana studies perpetuates the separation of Egypt from the rest of Africa. It privileges the people in Egyptology programs as “qualified” to speak about Egypt and, from the perspective of Egyptology, confers the opposite on people in Africana studies. That divide separated Du Bois, Hansberry, and other scholars from white Egyptology. We must not maintain that racist, divisive system.

References

Davies, Vanessa. “Egyptological Conversations on Race and Science.” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports, 2018. https://rockarch.issuelab.org/resource/egyptological-conversations-about-race-and-science.html.

Davies, Vanessa. “W. E. B. Du Bois, a new voice in Egyptology’s disciplinary history / W. E. B. Du Bois, une nouvelle voix dans l’histoire de l’égyptologie.” ANKH: Revue d’égyptologie et des civilisations africaines 28/29: 2020.

Du Bois, W. E. B. The World and Africa. [1946] 2015.

Du Bois, W. E. B. The World and Africa. [1946] 2015.