Presenting Ancient Egypt

The earliest religion in Kemet was animism. Like many traditional African religions, the Kemite version looked to nature in order to explain the world, and to provide spiritual support and protection. Animals played an important role within Kemite religion and were seen in two key capacities: (1) as representations of the gods on earth and (2) as symbolic guardians and protectors.

One particular aspect of this phenomenon was the subject of a special exhibition at Manchester Museum: Gifts for the Gods. Animal Mummies Revealed. As the title suggests, the exhibit explored the cultural context and composition of animal mummies, the latter through CT scans. Such technology has enabled museums to see what was inside the wrappings without damaging the actual item. In the Victorian period, when mummies (both human and animal) were first removed from their original contexts and placed in museums throughout the world, they would typically be unwrapped. The legacy of this practice can be seen in museums globally, especially in regard to the display of the remains of Kemite people.

Presenting the past

Any museum curator will tell you how difficult it is to balance the number of objects on display with the information that is presenting about them. Ultimately you are often left with a choice: do you display more objects or give people more information? Some museums have what are called open access displays. This is where all objects are accessible to the public in display cases but there are no explanations, dates or reference numbers accompanying them. I personally really like this type of display because you can see everything. However, such displays can cause frustration, especially if you want to know what something is or where it was excavated because you often can’t even find the registration number in order to write to the museum to ask them.

In the Gifts for the Gods exhibition, however, there was plenty of room for information provision. A large information panel entitled British Archaeologists in Egypt included an archive photograph of the Egyptologist John Garstang sitting in front of a union flag (above). Egypt was, of course, occupied by British forces between 1882 and 1952; and although the country retained its autonomy as part of the Ottoman Empire until 1914, British archaeologists and Egyptologists often raised their national flag at excavation sites. The text accompanying the photographs reads:

John Garstang’s workroom inside a rock-cut tomb at Beni Hasan, showing him seated to the right, 1902-4

I was disappointed that the opportunity was not taken to comment further on the colonial nature of this photograph or indeed the history of Egyptology. For visitors, such images have the potential to reinforce and accept Britain’s colonial past rather than to question and consider the consequences.

Addressing Britain’s colonial past

Upstairs in the the Manchester Museum was another exhibition entitled The phantoms of Congo River. Photographs by Nyaba Ouedraogo. Here, a label that accompanies material culture from the Congo River includes the following text:

These objects were collected from places and people along the Congo River from the late 19th century. Such collections are the legacy of European commercial and colonial interests in this part of Africa, the same interests that drive Charles Marlow in the novella Heart of Darkness.

These objects were also collected during a similar time period to those in the exhibition on Kemet. Why then is there such a discrepancy in the way in which this practice is presented in two exhibitions in the same institution? Is it not timely and appropriate for Egyptologists to adopt a more critical approach to the history of their subject? I would suggest very strongly that it is.

Idealised and Romantic (and Racist?)

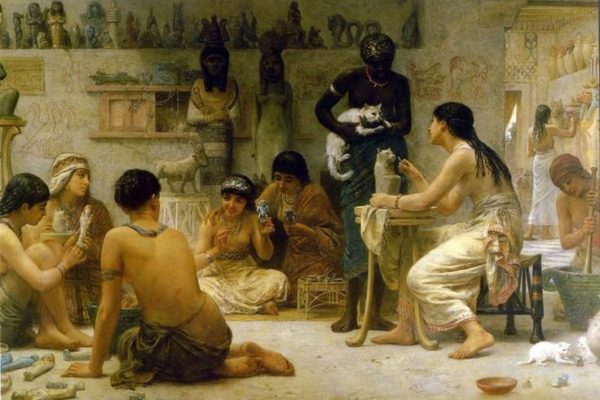

The painting above was used in the exhibition to illustrate a woman carving a statue of a cat. I was struck immediately by the appearance of the ‘Egyptians’ in the work, identified by the artefacts that they hold and who are clearly of European descent. The only African person to be represented in the painting is holding a cat, that is the model for the sculptor.The panel accompanying the painting read:

European paintings and literature of the 1800s portray an idealised, romantic version of ancient Egypt, inspired by impressive temple ruins. The vast numbers of animal mummies buried in catacombs were well know to travellers. This led to the mistaken belief, based on Western ideas about animals as pets, that the ancient Egyptians worshipped animals themselves rather than the gods they represented. The reality for many animals prepared as mummies was very different.

I am not suggesting that museums should not show such works, but they need to be presented through a critical lens, and the blatant racist ideologies that accompany such images need to be deconstructed. Otherwise there is a danger that visitors leave the space with a confirmation that this was a reality. By describing such works as ‘idealised’, ‘romantic’ museums are failing to address a colonial and racist past.

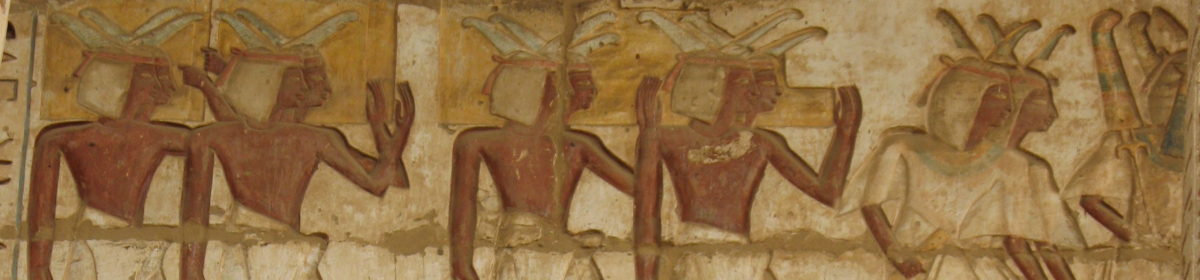

As a person of African descent, these Eurocentric fantasy paintings of not only Kemet but other African societies is rather tiresome. Especially when there are plenty of actual paintings from the walls of Kemet depicting actual Kemetic people creating said items (artifacts). These fantasy paintings are actually a slap in the face since we/Africans are usually depicted as servants and “helpers”.

As for the unwrapped mummies, I view this as a display of desecration. It is as if the body of Charles II was on permanent display in a Nigerian museum: I am sure certain Britons would be permanently up in arms. Thanks for your work, Dr. Ashton.

Thanks for sharing your thoughts and for the positive feedback. You are quite right when you reference that African people are often presented as servants or helpers. A couple of years ago, a make-up artist contacted me and asked me why the pigments that were used for make-up in Kemet seemed to be too strong in colour for the actors. When I asked what the racialised background of the actors who were playing the ancient Egyptians was, I was told they were White. I pointed out that this was the problem, that the colours were fine on darker skins. I was then told that there were some actors of African descent in the film and when I asked what parts they were playing I was told this servants and slaves! I pointed out that there was a problem with this. That if the servants were Africans then so were the kings, and any other level of society. She said that she would pass this information on to the director, but I doubt it made any difference.

Yes, I doubt it made it made a difference too. However, I’ve accepted the fact that this is the prevailing scenario in Hollywood and faux historical reenactments. I don’t find it remarkable that the reenactments for every other historical cultural seems to present the characters properly.

On a side note, I saw a youtube presentation that presented Mansa Musa and Mali to children with generic cartoon characters and the cartoons appeared to be “Caucasian” people. I actually let him know that his innuendo was irresponsible in regards to the children – especially with a teacher stating she would use that in her class.

Ethnocentric may call this petty complaining, but your eloquent thoughts on the fake outrage in regards to Cleopatra really has exposed this hypocrisy publicy.

I’m really surprised to hear about the misrepresentation of the people of Mali; I had always thought that it was just Kemet that was appropriated in this way. Did the person who made the presentation respond to your message?