Black history month and Kemet

As I noted in my last post, October is Black History Month in the UK. I knew that I would be busy travelling around the country giving talks, so I decided to tweet information and images relating to Kemet, rather than writing posts. I thought that I would write a little more about the image that received the most shares and responses.

On 11 October I tweeted the above image along with the name and date of the king and the simple statement:

The pigment and skin colours are original

The image comes from a temple at the site of Amada, in southern Egypt/Nubia. The temple was built in the 18th dynasty by King Thutmose Menkheperura, who ruled from around 1479-1425 BCE, and is one of the oldest surviving temples in this region. Further decorative reliefs were added by Thutmose’s successor: Amenhotep Aakheperure; and some restoration was carried out later by kings of the next dynasty. The temple is dedicated to two gods: Amun and Ra-Horakhty.

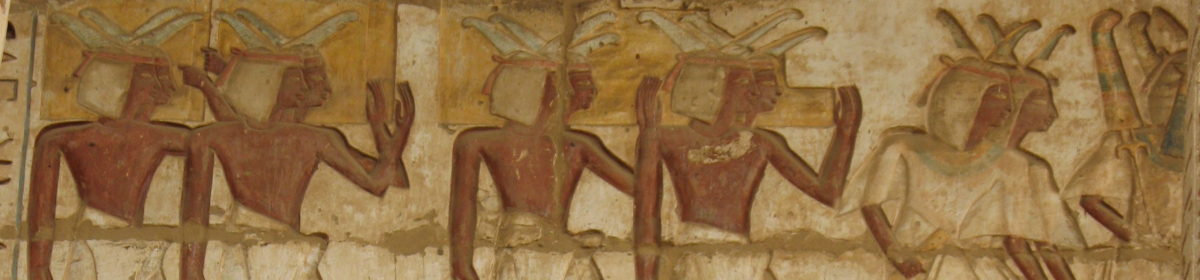

In the relief above, the king (right) is shown in a dynamic running pose, in his hands are wine jars. On his head he wears the crown of Lower Egypt/Kemet.

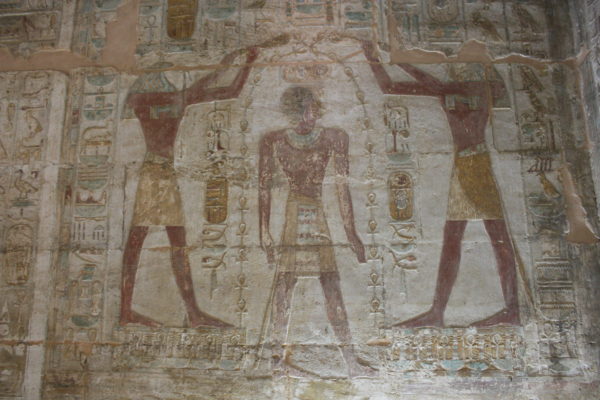

On the relief above the king stands in the centre and Djehuti (left) and Ra-Horakhty (right) pouring liquid in the form of the ankh sign over him, demonstrating his right to rule and his status and power as king. There are other ritual scenes on the walls of the temple. Below is a representation of the King in his role as head priest. He is accompanied by other priests who carry the barque that contained the image of the god. Note the animal skin garment that the head priest wears, he stands behind the king.

This small temple may not be impressive as some of the larger complexes in the southern parts of Kemet, however, the scenes enable us to understand more about the role of the king and his relationship to the gods. The pigment (colour) is incredibly well preserved in parts of the temple and show very clearly that the people represented had dark brown skin. There are scenes, such as the relief showing the later king Rameses Usermaatra-Setepenra, who presents an offering to a figure of Amun. The skin of Amun is painted black, and is used symbolically to represent fertility, and his consort is shown with gold-coloured skin representing her divinity. The king’s skin is dark brown, which we must conclude was close to its actual colour, as it was for other rulers on the temple’s reliefs.