The psychologist Stanley Cohen described moral panic as “a condition, episode, person or group of persons emerges to become defined as a threat to societal values and interests.” (Cohen, 1972, p. 1). The casting of a bi-racial actor in the role of Cleopatra for a Netflix docu-series has prompted accusations of “blackwashing” history and arguably a state of moral panic, which the media has (largely) endorsed.

This isn’t the first time that such a response occurred. In 2008 I was involved in a project to digitally reconstruct Cleopatra. The process (described here) prompted an unfavourable response from some groups because the reconstruction showed a young woman with a darker complexion and African-type hair. It used to surprise me that so many people with no formal training in either classical archaeology/art history or Egyptology felt that their opinion was a reality. Fifteen years later and some people are responding in exactly the same way. Of course nobody can know for certain what Cleopatra looked like. We have representations of the ruler from during her lifetime, but the extent to which these reflected her true appearance remains uncertain. However, the point of contention for many has really been her perceived ancestry.

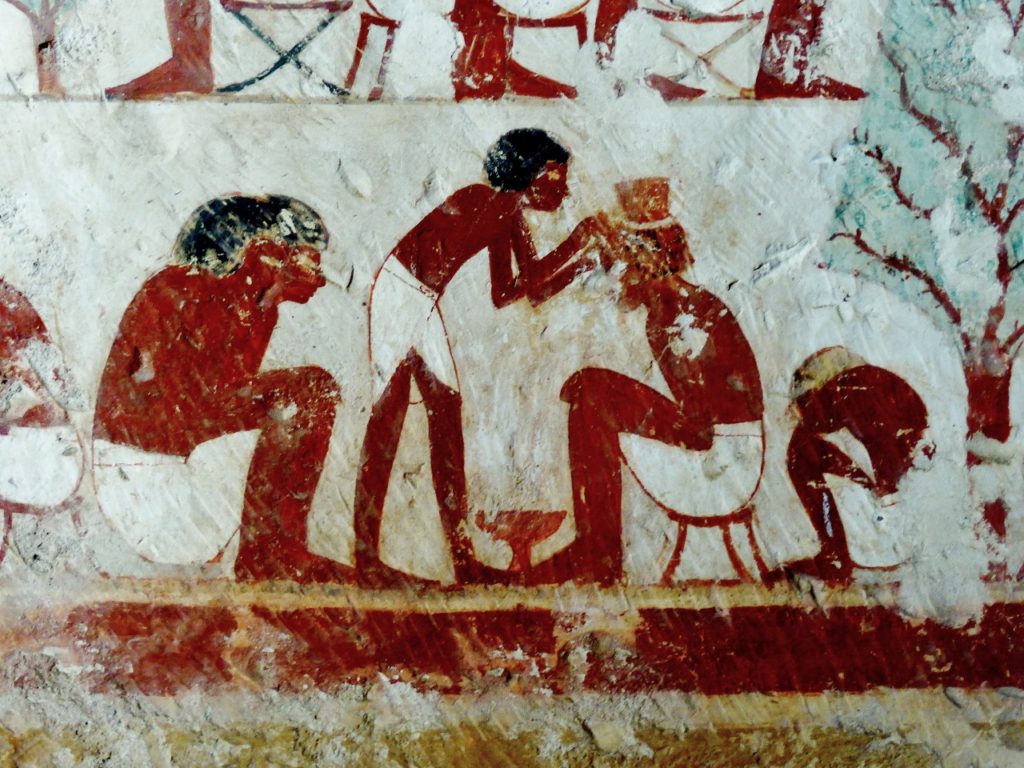

The same people who criticize the presentation of Cleopatra as “Black” (I will be deconstructing this later in the post) insist that she was”light skinned” and “white”. It isn’t helpful to apply modern racialized terms of “Black” and “white”, especially when they were meaningless to ancient people. Cleopatra was descended from Macedonian Greeks who were immigrants to Egypt. This much is clear. However, it is possible that her mother and grandmother were Egyptian (their identity is unknown). Leaving those modern racialized terms aside, if we look at depictions of ancient people from the Nile Valley their hair is black in colour and coily/curly and their complexions range from light brown to dark brown.

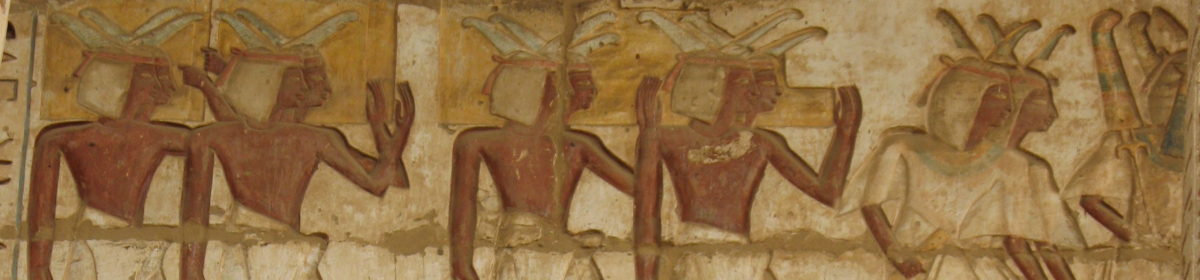

Ancient people from Greece and Rome showed the people from the Nile Valley in the same way the Egyptians had depicted themselves for thousands of years. Paintings from the Temple of Isis in Pompeii show Egyptian priests with a darker complexion (see below); their hair shaved for the purpose of purification during rituals. The priestesses and members of the cult who were depicted on the walls of the Roman temple are shown with a range of complexions. Italy under the Romans and Egypt in the Ptolemaic and Roman periods were multicultural societies and were not bound by modern concepts of racist hierarchies.

Ethnicity vs “race”

Cleopatra was bi-cultural (Egyptian and Greek). However, she chose to present herself exclusively according to Egyptian culture in her homeland. Her Greek-style royal imagery was preserved for coinage (an international currency). It was this style of representation that was adopted for contemporary and posthumous portraits of the queen in Italy.

The Ptolemies, who were ethnically Greek had ruled Egypt for over 250 years at the time of her birth. For their first century of rule they had balanced their presentations separately as Greek kings/queens and as the Egyptian royal family. This was doubtless to muster political and religious kudos among the indigenous priesthood, who were a powerful and educated class. Adopting the Egyptian concept of kingship awarded the rulers a deified status that had hitherto been reserved for deceased mortals in Greece. By the reign of Ptolemy V many Egyptian-style representations of the king borrowed from Greek-style portraits of the rulers. Temple reliefs continued to be decorated with purely Egyptian style images of the rulers; their names translated in hieroglyphs.

Ethnicity is a cultural identity. Many recent commentators are confusing this with the modern concept of racialized identities. It is possible to be multi-ethnic (multi-cultural) and indeed this was recognised in Ptolemaic Egypt where Greeks and Egyptians married and had families. Any research on Ptolemaic society shows this to be the case. However, unlike her predecessors we only have evidence of Cleopatra depicting herself in Egypt as an Egyptian. As noted, her presentation overseas catered to a European audience and was essentially different.

Taking account of the possibility that Cleopatra’s mother and grandmother were Egyptian people, it seems plausible to present her as someone who is part European and part Egyptian (African). In modern racialized terms- as bi-racial. It is therefore notable that those who object to this premise claim that Cleopatra could not have been “Black”. The argument that she was descended and culturally Greek are irrelevant to her racialized identity. Moreover, it is the same people who have decided that a bi-racial Cleopatra is “Black”, perpetuating the so-called ‘one-drop rule’ used historically in the US. By recognising that Cleopatra may have had an Egyptian mother and/or grandmother it places the ruler more directly within an Egyptian historical context rather than removing her, as has been claimed.

For those who state that the Ptolemies married their siblings- this is true until the time of Ptolemy XII (Cleopatra’s father). He was illegitimate and refereed to as a “bastard” (nothos). Why then is it so far stretched that Cleopatra could be part Egyptian? A more pertinent question should perhaps be- why do people need Cleopatra to be racialized as “white”? I will consider this from a psychological standpoint in my next post.