The meaning of the royal cobra

More commonly known by its Hellenic name of uraeus, the iaret or rearing cobra is synonymous with the goddess of Lower Egypt- Wadjet. The symbol was adopted by the Kemite kings and from the Middle Kingdom the rulers always wore this image on their brows. The iaret served two purposes: first, it referenced the King’s rule over the northern part of Kemet; second, it protected the royal representations and so the king.

On some royal representations from the New Kingdom, the cobra appears with the vulture, representing the goddess Nekhbet, who was the southern counterpart of Wadjet, together the goddesses were referred to as the Two Ladies (Nebet Tawy), which became the title for the Nebty name of rulers. Only one group of rulers wore the double cobra: those of Dynasty 25, who ruled Kemet and Kush simultaneously. It is thought that the dual iaret representing the two regions and that this is why it is only found on male rulers dating to this period.

Royal Women of Dynasty 18

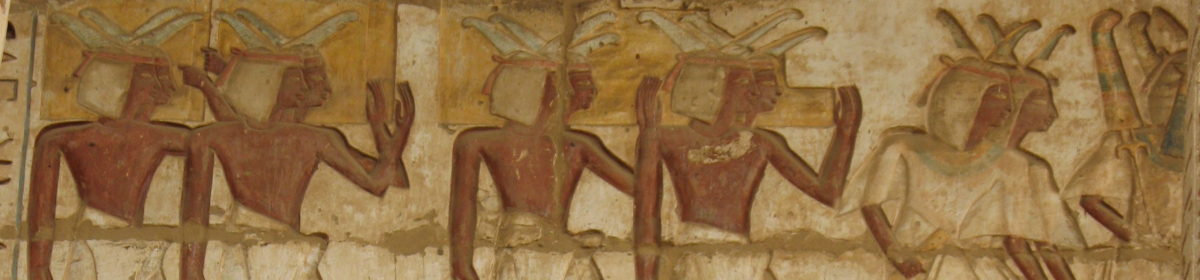

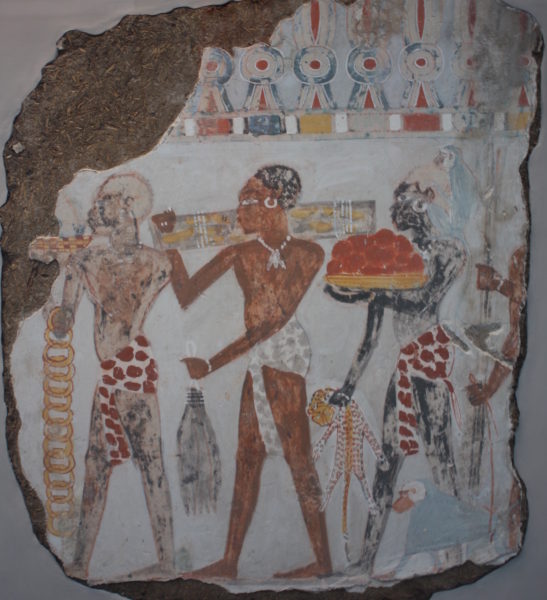

Royal women generally wear a single cobra on their brows; however, when elevated to a goddess, they were awarded the vulture for protection and to recognise their status. This can be seen on the wall painting above where Ahmose Nefertari wears both a vulture and a cobra, representing her royal and divine status.

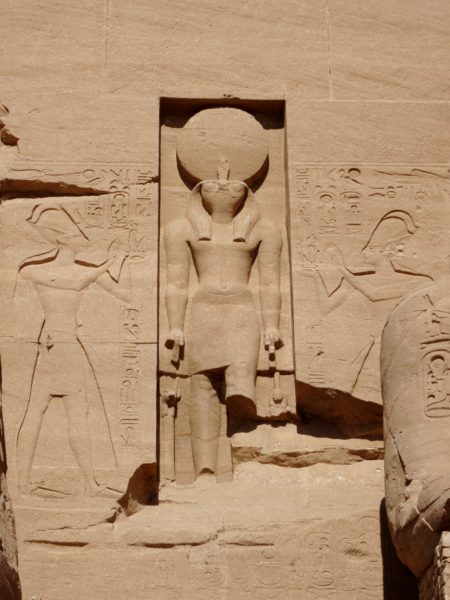

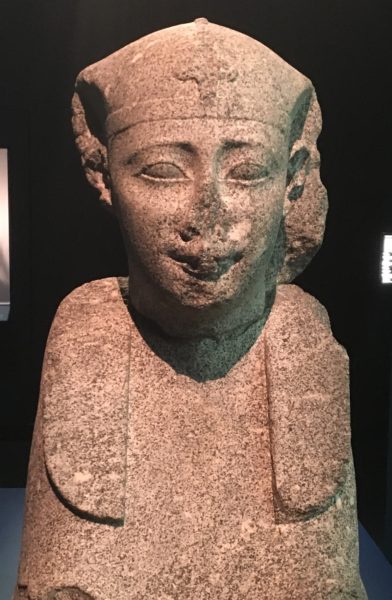

The first royal female to wear two cobras was Iset, who was the wife of Thutmose (II) Aakheperkare (1492-1479 BCE) and mother of Thutmose (III) Menkheperre (179-1425 BCE). On the statue above the Iset takes the title Mother of the King, and it is possible that the dual cobras were intended to distinguish her in this role as opposed to royal wife; unfortunately not enough statues survive to know whether she consistently wore the dual version of the royal motif.

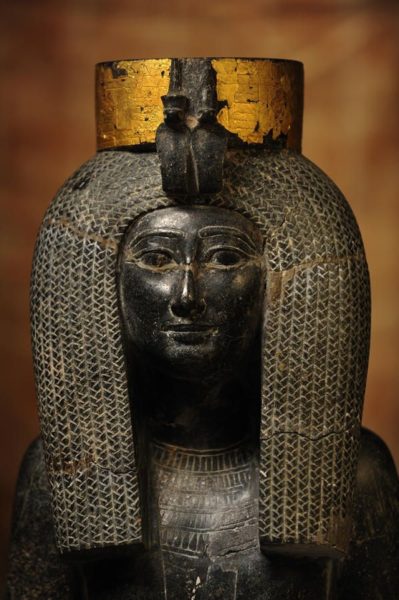

Royal Wife of Amenhotep Nebmaatra (1388-1351 BCE)- Tiye- wore two cobras and a vulture on her representations. As you can see from the statue above, the cobra and vulture wear their appropriate geographical crowns thus representing the unification of the Two Lands of Kemet. The central figure of a vulture appears because the royal wife wears a full vulture headdress- if you look carefully on the statues above and below you can just seen the feathers of the vulture’s wings sitting on top of her hair.

Even the smallest of representations of this queen bore the same iconography, as illustrated by the small faience figure above. It is possible that Tiye adopted this iconography after the Thirty Year rule of her husband was celebrated- the Heb Sed festival. We know that she initially wore a single iaret and that the famous wooded statue of the royal wife (below) was adapted at some point and the single cobra replaced by two.

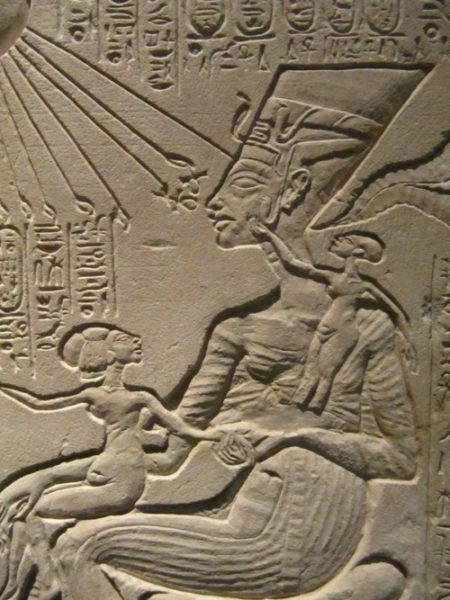

Possibly following on from Tiye, Nefertiti who was wife of Akhenaten Neferkheperure-waenre (1351-1334 BCE) in the early part of their reign also adopted the dual cobras, but not the vulture. And on the famous relief (below) the royal wife is shown with 3 cobras around her crown; and one of the royal children plays with one as if it were alive. This changed in the later years when the single cobra was used for her representations.

Royal Women of Dynasty 18

Nefertari, Principal Wife of Rameses Usermaatre-setpenre (1279-1213 BCE) in Dynasty 19 continued the tradition of wearing the double cobra, as seen on the colossal statue below and most of her other sculptures. During this period the double form seems to have been used to distinguish her as the Principal Wife.

Royal Women of Dynasty 25

As noted the Kings of Dynasty 25 wore two cobras on all of their representations, and were the first royal men to do so. The royal women during this period who were associated with the motif also had the elevated role of being the wife of the God Amun/Imen. On the tomb chapel of Amenirdis she and her successor Shepenwepet both wear the crown of the god (above). As goddesses on the relief the two women are shown with the divine vulture and headdress. However, on statuary they were shown with two cobras and a vulture. It seems likely during this later period that the double cobra and vulture were associated with title and role of God’s Wife of Amun/Imen.

Meaning of multiple representations of the iaret

For the male rulers of Dynasty 25 the dual iaret seems to be associated with the two kingdoms of Kemet and Kush, and this is certainly the conclusion that most Egyptologists draw, not least of all because it appears on sculptures in both kingdoms.

The dual iaret seems to have been reserved for royal women who fulfilled a particular role and is actually not at all commonly found. It can be associated with the roles of God’s Wife, Principal Wife of the King, and King’s Mother. Later in the Ptolemaic Period a triple form appeared. What this tradition shows is the careful consideration that went into representing members of the royal family and that this practice was ever-evolving, through until the last resident rulers, their wives and mothers.