Understanding African-centred Egyptology Lecture 2016

It was great to see so many friends at my recent London lecture for Black History Month, which had been organised by the Equiano Society and the British Museum. Some people who were not able to attend asked me if I would summarise the talk, so that is what this post will do.

I began by talking about the lack of theoretical frameworks within Egyptology and illustrated this point later in answer to a question with the dating of the sculpture in the current exhibition: Sunken Cities. Egypt’s Lost Worlds. The statues above form part of this exhibition and are dating the Early Ptolemaic Period by the curators. However, I would suggest, based on parallels, that this in fact represents Ptolemy VIII and one of his wives. I’m not suggesting that my interpretation should be taken over that of the curators of the exhibition. However, I used it to demonstrate that if we had solid frameworks on which to date and interpret the material culture of Kemet, of Egypt at this time, then there would be no such debate.

Of equal importance is the extent to which the lack of academic frameworks increases the likelihood of confirmation and cognitive bias.

Conspiracy

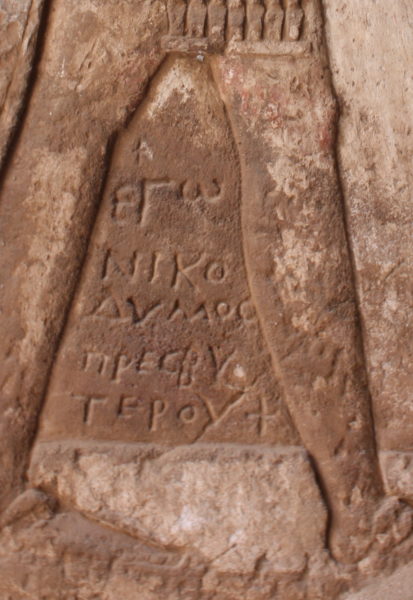

I then when on to consider popular conspiracy theories relating to the the ‘Whitewashing’ of Kemite culture; one of the most common is that European travellers deliberately removed the noses of statues in order to alter their appearance. I wrote my first post on this subject; debunking this particular myth, which risks distracting from embedded racist ideologies within the foundations of Egyptology as an academic discipline. The conspiracy to maintain an erroneous connection between ancient Egypt and non-African civilisations is much deeper than damaging statues.

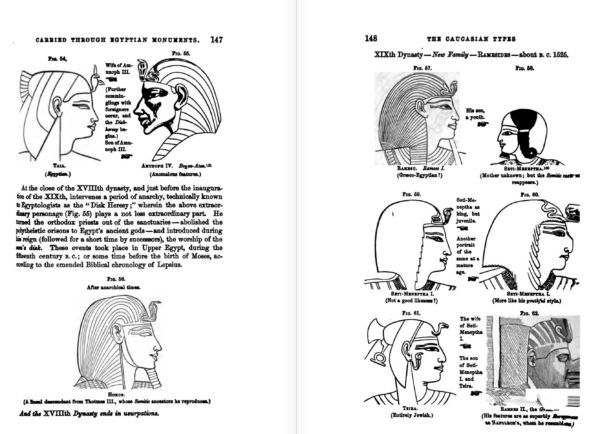

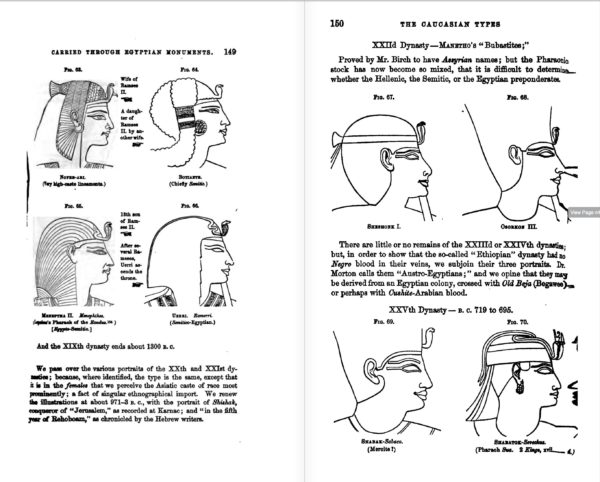

The illustrations above are from Nott and Gliddon’s 1854 publication on ancient Egyptian monuments. In it, they argue on the basis of nothing but their own prejudice and supremacist ideologies that the people of Ancient Kemet were non African. Here rulers are described as “entirely Jewish” and the caption that accompanies the drawing of a statue of Rameses Usermaatre-setepenre reads:

His features are superbly European as Napoleon’s, whom he resembles.

I have taken the liberty of including an actual statue of the King below!

They continue with their racist ideologies throughout the book. And a summary of 3 out of 15 points in the book of their colleague Samuel Morton goes some way to explaining why these early authors were so keen to remove Egypt from Africa:

1.The valley of the Nile, both in Egypt and in Nubia, was originally peopled by a branch of the Caucasian race.

7.The Copts, in part at least, are a mixture of the Caucasian and the Negro in extremely variable proportions.

8.Negroes were numerous in Egypt but their social position in ancient times was the same that it now is, that of servants and slaves.

S.G. Morton, Crania Aegyptiaca, or, observations on Egyptian Ethnography, derived from anatomy, history and the monuments 1844: 65-66

Quite simply these writers were projecting their own distorted sense of the world upon the past.

Keeping up appearances…

Museums have a choice. They can either perpetuate the myths that were peddled by past scholars who belonged to a racist imperial past. Or, they forge ahead with a more appropriate presentation that shows the African origins of this ancient culture as well as the cultural diversity in the region across time. In actual fact in order to understand the history of Egypt you have to do just this.

This can be as simple as including a map of Africa and reminding people that Egypt is an African culture with indigenous African people as a population. The screen at Manchester Museum achieves this by situating Egypt in Africa.

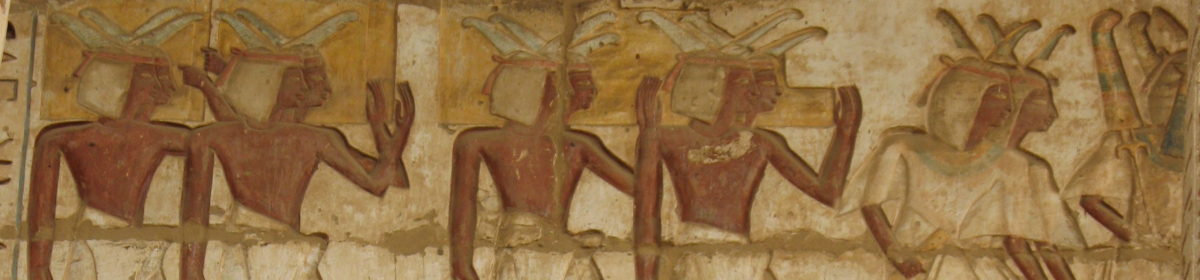

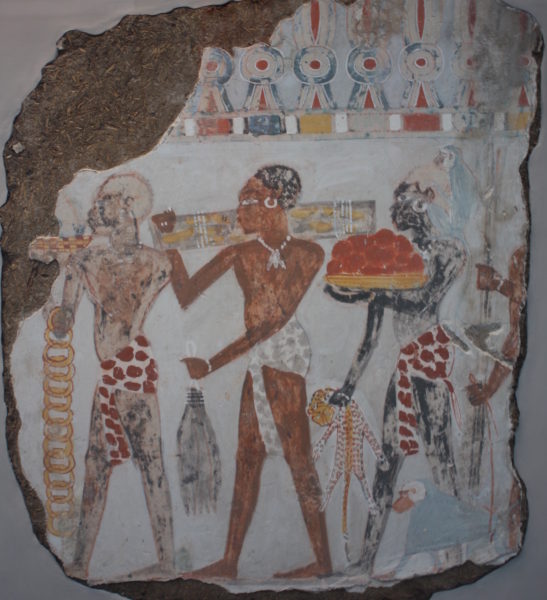

I went on to discuss how identifying only certain figures from ancient Kemet as African was really no different to the categorisations of Nott, Gliddon and Morton above. At the British Museum only one room is explicitly linked to Africa; this is the room that contains material from the region of Nubia and which includes images like the tomb painting below that depict people from this region.

By making a distinction between people from the region of Nubia (ancient Kush) and Kemet, Egyptology erroneously implies that there is one ‘type’ of African person. Could the figure below not also be seen as a representation of an indigenous African person? I would suggest so on the grounds that her hair is textured and is a style that is not found outside of African cultures.

I have discussed possible solutions elsewhere on this blog. However, as I concluded in my lecture, until those who study Egyptology look more widely for cultural parallels and frameworks, it will continue to perpetuate a myth that engenders a divisive interpretation of the past. It feels odd to have to defend this culture as African, and yet in 2016 we are still having to do so.