Background to the project

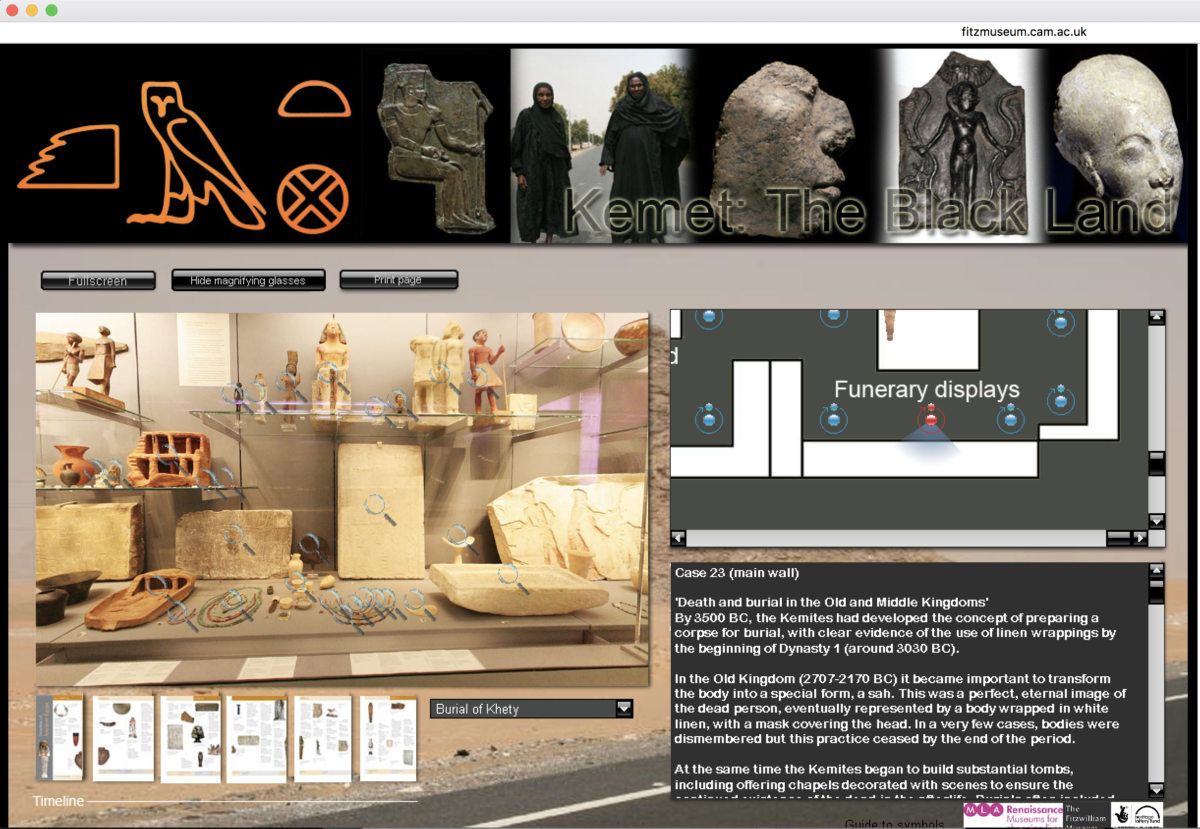

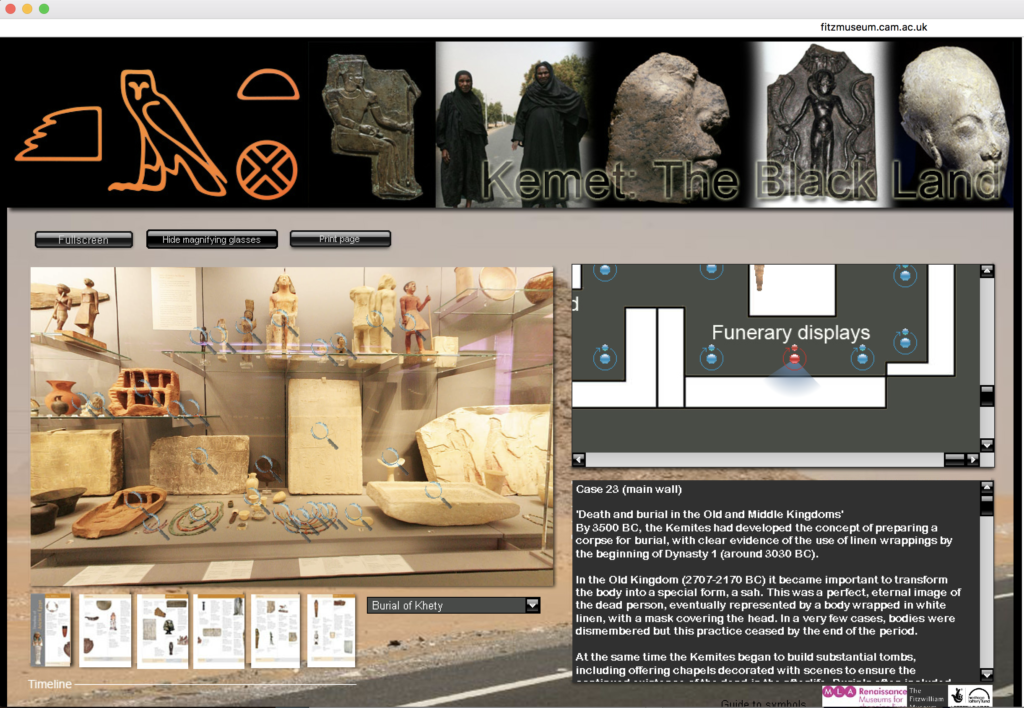

In 2016 I wrote a blog post sharing a resource that I had worked on during my time as a museum curator at the Fitzwilliam Museum, which is part of the University of Cambridge. The idea for the virtual version of the Egyptian galleries came from a project that was based in English prisons. With the support of the Museum I applied for funding to provide resources for the public and for those who were incarcerated (the final version was saved in a format that could also be shared with prison education departments).

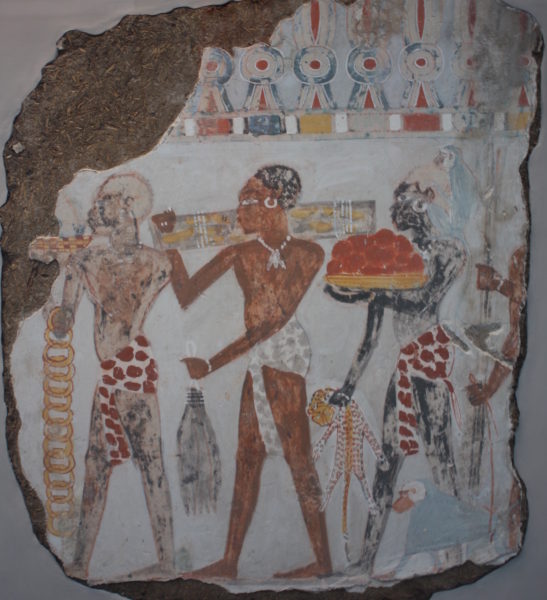

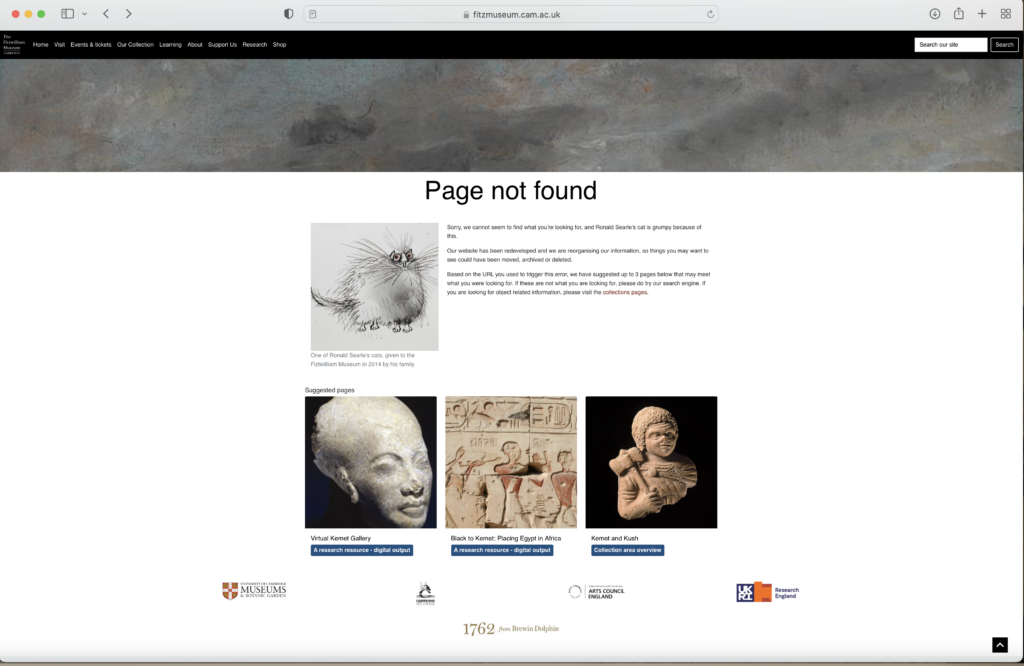

Virtual Kemet was the first of a number of African centred digital projects that I worked on during my 13 years at the museum. Others included photographic exhibitions on Nubian culture, temples in Egypt and Nubia, and the Origins of the Afro Comb project. Over the years many community members have contacted me to say how they found these resources useful for family learning, teaching, and (for some of those who were incarcerated) self-reflection. I was therefore surprised when people started contacting me saying that they could not longer access materials. Initially this related to the Origins of the Afro Comb Project web pages, which had be transferred from an external site to the museum’s pages. When members of the public tweeted to inform the museum, it responded by salvaging as much of the site as possible, this included museum objects but excluded all of the community stories that were meant to be archived as part of the project’s legacy. A search (below) on the website shows that none of the pages can be found.

Who controls access to knowledge and culture?

The longevity of digital cultural materials has long been recognised as a problem within museum and archive research. Funding often only covers the initial site and content formation and so subsequent maintenance relies on institutions to either apply for further external funding or to use core funds to finance continued access. There are, however, additional factors that need to be considered in regard to the allocation of funds to past projects. First, if the original curator is no longer at the institution it is less likely to receive the same attention or focus as work that is supported by a current member of staff. That is unless the institution is invested in the research and work. Directors, curators, and researchers alike will be more invested in their own research and exhibitions. Second, in institutions where the relevant community’s voice is unrepresented, culturally specific projects are less likely to be prioritised. Whereas there is little that can be done to change the outcome of the first point because it relates to the psychology of individuals. The second observation can the extent to which an institution is willing to decolonise the presentation of its collections. Both positions award cultural institutions a degree of power and control.

The case of virtual Kemet

When I realised that all of the resources were missing I contacted the museum. As noted, part of the Origins of the Afro comb site had been retrieved and made accessible. I was told that the Virtual Kemet site was no longer compatible and so it had been removed. Regarding the community comb stories and the other project sites, their content has apparently been lost. Fortunately, I retained copies and I have offered them to the museum. However, I was told that this could not be processed internally and would require a commitment of funding. My enquiry was immediately acknowledged by the member of the senior management team who I approached, but was ignored by the relevant second Deputy Director. Several months on from this conversation, the material remains inaccessible. The research for these resources was funded from external sources such as The Heritage Lottery, The British Academy, Arts Council England, Arts and Humanities Research Council, The Lankelly Chase Trust, The J.P. Getty Trust. It is fair to say that the focus on community engagement and outreach to vulnerable communities that I successfully undertook between 2003 and 2015 (with the support of the museum’s education team) brought kudos to the museum and University, as recognised by their promotion of my research at the time. The case of virtual Kemet raises important questions relating to how communities access their cultural heritage and whether museums actively and comprehensively decolonise the presentation of their collections.

In 2020 University of Cambridge Museums publicly declared their commitment to decolonising their collections writing:

“We stand in solidarity with Black Lives Matter, with our Black friends, colleagues and visitors. As museums, we haven’t always been there. We should provide respectful spaces for everyone to be heard, share learning, and enjoy. But our collections were founded on and exist within unequal power structures. Without addressing this, we will continue to entrench that inequality.”

The declaration notes that “there is a long way for us to go. We are absolutely committed to going the distance”.

So this raises the question of whether Kemet is not viewed as a valid part of this process. The progress of decolonising this particular part of their collections was well under way long before 2020. It seems not only to have stalled but, for the most part, now been lost. Tackling colonial legacies and institutional racism takes more than a statement. It requires long term commitment and strategies to ensure that people can access their cultural heritage on their own terms and with the broadest possible scope.