The announcement in mid-October that Gal Gadot would play the last Cleopatra in a new film provoked responses of whitewashing and reports of a ‘backlash’ in both social and the mainstream media. There were those who commended the casting and those who found it inappropriate for two key reasons. The first objection related to Gadot’s nationality. Social media commentators felt that it was insensitive to cast as Israeli national as the ruler of an Arab nation (I will come back to this in due course). Second, was the question of Cleopatra’s racialized identity and the possibility that her mother and grandmother were indigenous Egyptians rather than Greeks.

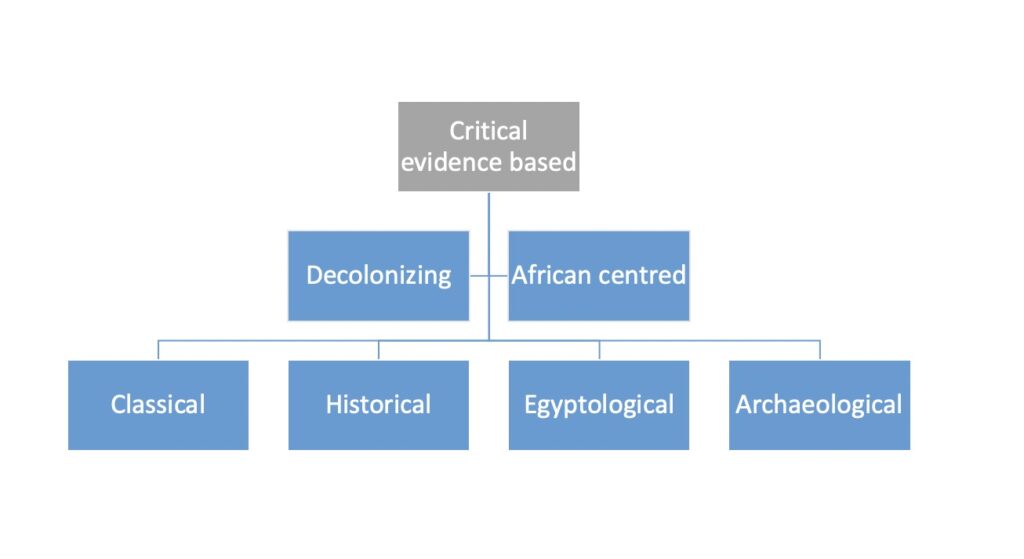

The issues with the casting therefore relate to Cleopatra’s ethnicized and racialized identities. I was interested to see if the responses (academic and general) could be categorised into frameworks in order to see which approach offered the most appropriate and inclusive response.

Response categories

Classical

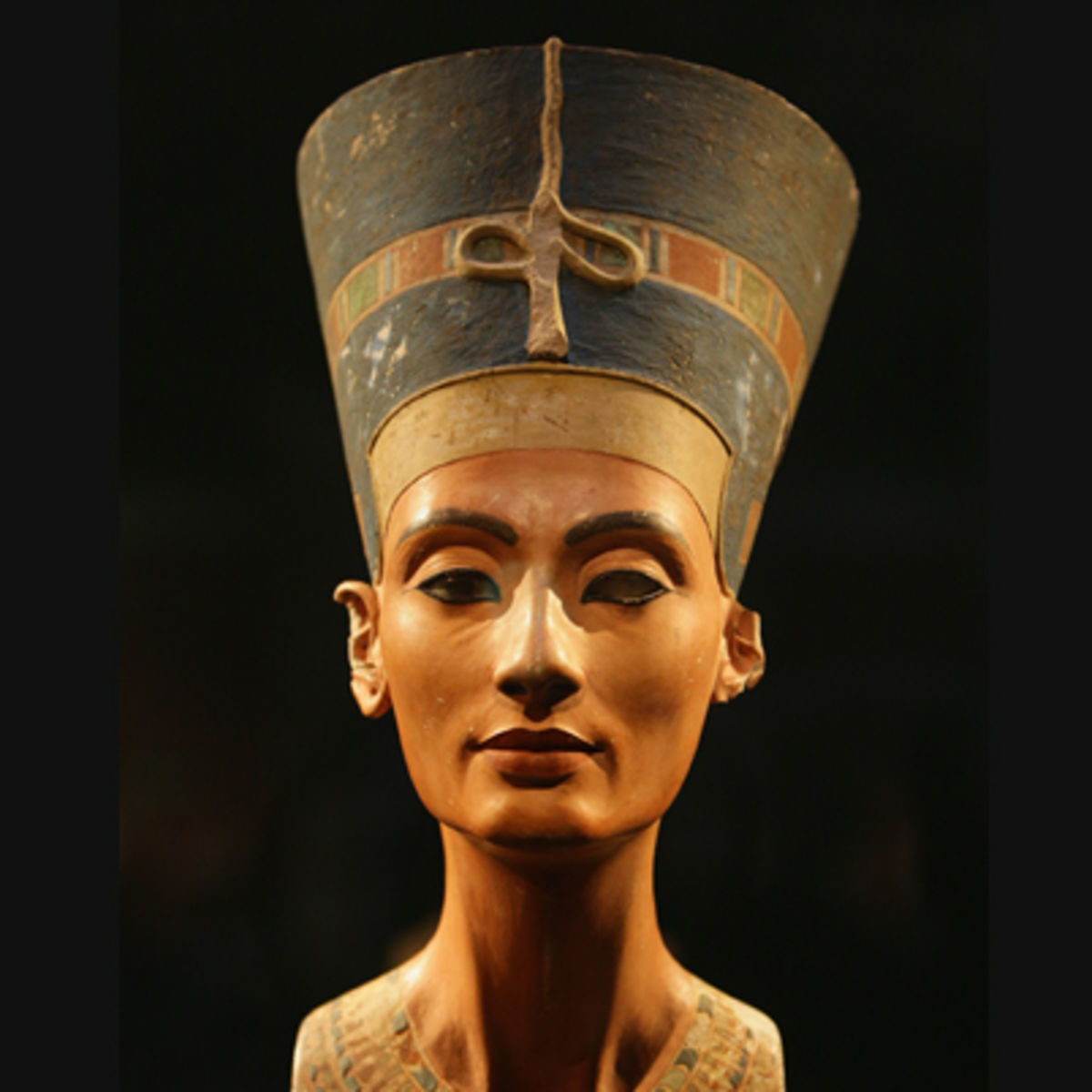

The Classicist (used here to describe the adopted approach irrespective of training) responds by describing Cleopatra as a Macedonian Greek. This effectively restricts both identities to European and Hellenistic Greek.

Historical

The Historian (used here to describe the adopted approach irrespective of training) uses texts to effectively remain impartial whilst acknowledging that there are questions relating to the identities of her mother/grandmother. The typical response is that we will likely never know what she looked like (or her racialised identity). This approach does not consider Cleopatra’s ethnicized identity.

Egyptological

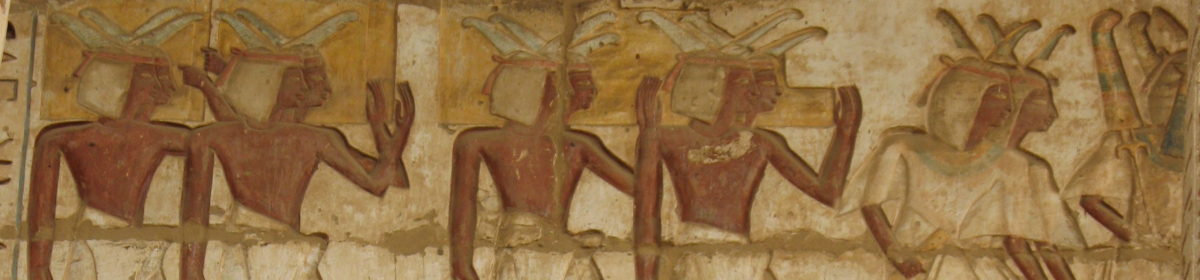

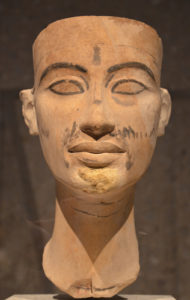

The Egyptologist (used here to describe the adopted approach irrespective of training) can situate the evidence of Egyptian material culture within a traditional framework. However, given the wider debate around the racialized identity of the people of ancient Kemet, the approach is largely concerned with Cleopatra’s ethicized identity. The Egyptological approach is essential because without understanding how Cleopatra was presented in her home country, it is impossible to fully understand her image overseas.

Archaeological

The Archaeologist (used here to describe the adopted approach irrespective of training) has the ability to expand upon both identities through studying the material culture from Egypt and overseas. This approach can include the identification of human remains, which could answer the question of Cleopatra’s racialized identity. We do not know where the ruler was buried. However, the remains of (what is assumed to be) her sister in a tomb at Ephesus have supported that some members of the family were of mixed African and European ancestry.

Critical approaches

Two dominant critical approaches have also emerged from the recent responses to the announcement of the new film. The first seeks to decolonize more generally and it has been suggested that an actor of Arab descent should play the role of Cleopatra. A fundamental issue with this association of course is, as I have noted, that Cleopatra ruled in Egypt long before the Arab settlement in North Africa. If the maternal side of her family were indigenous women this should be reflected in any contemporary representations of Cleopatra. This brings me to the second approach, which is to consider the ethnicity of Cleopatra within an African centred context. The evidence from Egyptian archaeology and material culture supports this as a valid option; Cleopatra was only presented according to Egyptian (Kemite) traditions. This included her representation at the Temple of Isis in Alexandria (seen as a Hellenistic city), where she and her son are depicted in Egyptian-style statues.

And the film?

Cleopatra (VII’s) father was referred to as nothos (illegitimate) and the identity of her mother has been questioned by historians. It has been suggested that both women may have been Egyptian and so African. With this in mind, at the very least, the film makers should have considered an actor of mixed ancestry to play the role of Cleopatra, and that this would have been a valid choice. Many institutions and industries are finally recognising the importance of correctly acknowledging the presence and achievements of people of African heritage. This would have been a perfect opportunity for the Film Industry to promote Cleopatra’s position as an African ruler of dual ancestry.