A curious statue

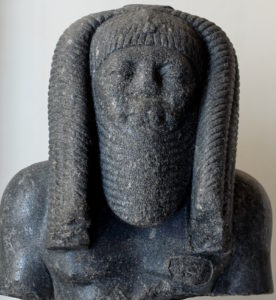

Not only is this statue unusual in its form, but it was first recorded in the 16th century (common era) by the Renaissance architect and antiquarian Pirro Ligorio at the site of an Ancient Roman temple in Rome, Italy called the Pantheon. This was not, however, where it had originated.

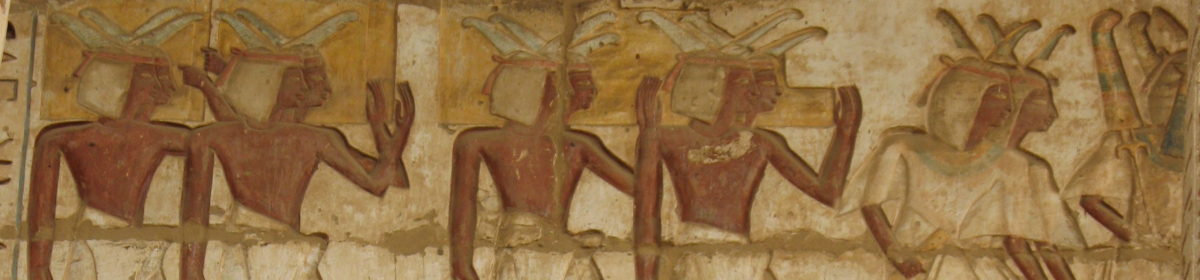

The statue represents a much early king of Kemet: Amenemhat Nimaatre, or Amenemhat III as he is generally called today. Amenemhat was the sixth ruler of what we now refer to as the Twelfth Dynasty and ruled Kemet for around 45 years from 1859-1813 BCE. He is perhaps best known for the pyramids he built in the region of the Fayoum. There is a second statue that shows the King with the same hair and beard. This statue (below) was found at the site of Tanis and is in the form of a double representation that shows Amenemhat as a marsh deity (god). It is inscribed with the title “The offering bearers of Tanis”. References to the marshes can be seen on the tables in front of the King; they are decorated with plants and fish.

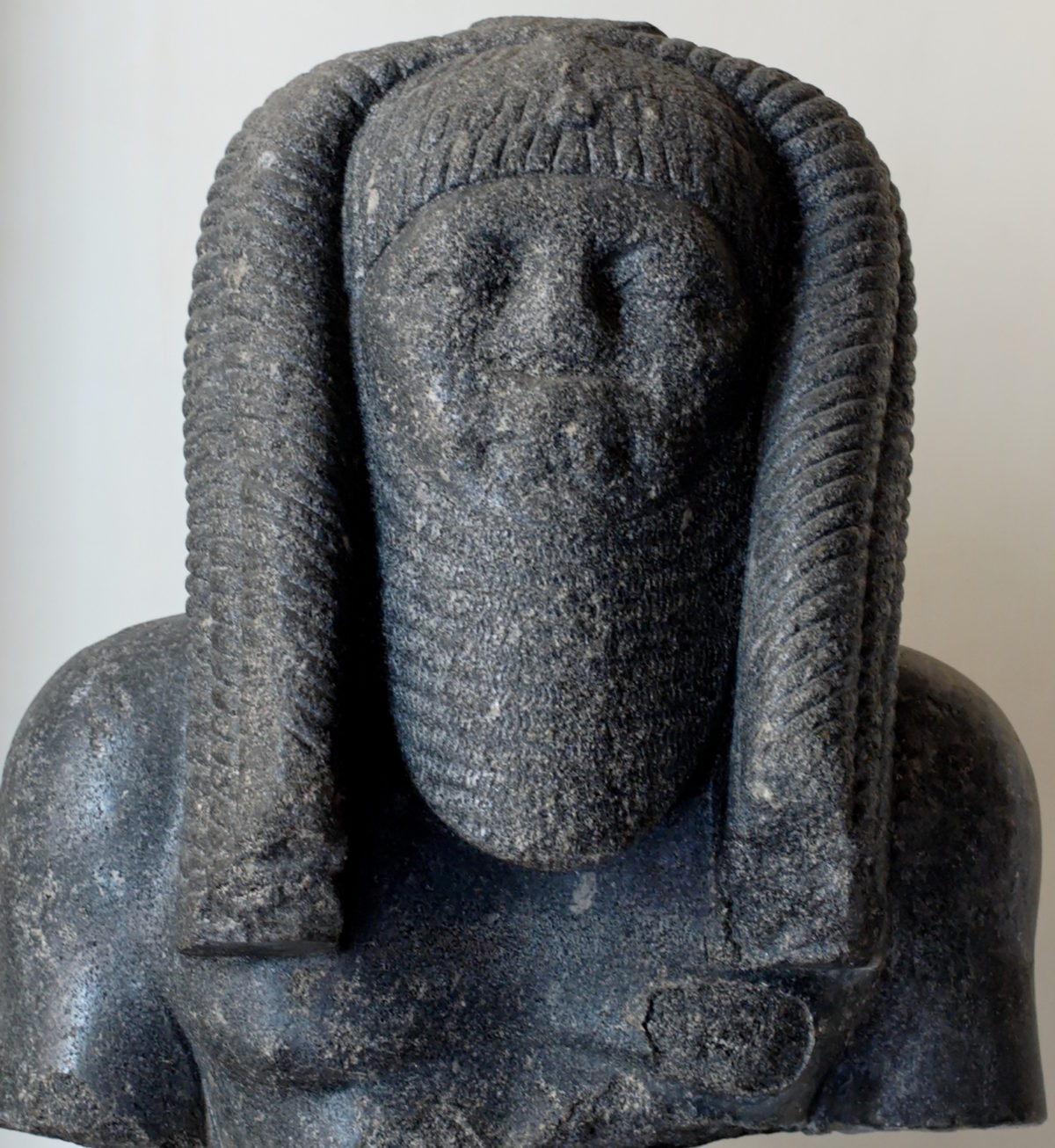

I remember seeing this statue in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo when I first went to Egypt, when I was still studying Classics and before I knew anything about Ancient Kemite art. It stood out from all of the other statues in the museum and I recall being struck by how unusual it was.

Both statues show the king with thick locks of hair cascading down from a shorter twisted style at the front of the head. The sheer volume of hair suggests that the hair type was African, and this is confirmed by the two types of locks that create this incredible hairstyle. The beard is also unusual in its form but complements the head hair.

The facial features on both the Cairo and Rome statues are strong and typical of this period. The broad face, strong cheekbones, and wide nose are reminiscent of the portraits of the previous ruler of the Twelfth Dynasty Senusret Kakaure. Suffice to say that the shorter hair style and the facial features that appear on Amenemhat’s statues are those that are typically now categorised as ‘Nubian’.

From Kemet to Rome

As noted, the statue of Amenemhat was first recorded at the Pantheon in Rome (above). In fact, it had originally been placed in the largest Egyptian temple in Rome: The Iseum Campense. There had been a cult to the goddess Isis at the site of the Iseum before the Roman’s took control of Kemet. However, the emperor Tiberius, who ruled from 14-37 CE, destroyed the sanctuary following a scandal involving a man named Decius Mundus. Decius pretended to be the god Anubis and seduced a devotee of the cult of Isis named Paulina. When she discovered the truth Paulina complained to the emperor, who responded by throwing all of the statues from the temple into the River Tiber. The sanctuary continued to have chequered history. It was was rebuilt by the Emperor Calligula (37-41 CE), burnt down during the reign of Titus in 80 CE, and then rebuilt by the emperor Domitian (81-96 CE).

It was probably during the reign of Domitian that the statue was brought over to Italy from Kemet. Domitian was a strong supporter of Egyptian cults, especially Isis. It was typical of such cult centres to have a combination of both ancient statues from Kemet and newly manufactured representations of the emperor as an Egyptian king.

As for Amenemhat, he was worshipped as a god in his own right in Kemet during the Ptolemaic period (332-30 BCE), possibly even before. In the Late Period there was a renaissance that looked back to the period of the reigns of Senusret and Amenemhat. During this period artists even copied the portraits and styles of statues that were produced in the earlier period. Whether the Romans who took the statue from its original location were aware of this tradition, we will probably never know.